THE BIOMEDICAL SECURITY STATE, Part One

This is the first in a series of three on the Biomedical Security State: Digital ID; Central Bank Digital Currency; the New World Religion of Transhumanism.

I am not a number. I am a free man. #6, The Prisoner

In the 1960s TV show, The Prisoner, Patrick McGoohan’s character is an unnamed British intelligence agent who resigns from his job for reasons never explained, is gassed, and wakes up imprisoned in a deceptively lovely place called The Village.

He is assigned the number Six to identify him. In the first episode, he meets with number Two, who tells him, “The information in your head is priceless. I don’t know if you realize how valuable a property you are.”

In that first meeting, number Six finds out that “they” have been monitoring him his whole life. Number Two tells him, ‘There’s not much we don’t know about you, but one likes to know everything.”

This obsession with “knowing” has been going on for thousands of years. To be reduced to a number so that we can be more easily studied and categorized. To lose our individuality, while at the same time being told we are important because of the information we carry inside of us. What does that do to a person’s sense of self?

It seems that the more we “know” about ourselves, the less real we become. Perhaps the natives were on to something when they refused to be photographed, believing that the cameras were stealing their souls. Each time we offer more of ourselves into technological devices, do we become less of a person out here—in the “real” world? What is real? Do we even know anymore? They used to say, “a picture is worth a thousand words.” But pictures can make fantasy real now and reality fake.

Identification has evolved over thousands of years from physical symbols and skin markings or tattoos, to the written word and now, to biometric verification. You could say humans have always been obsessed with statistics, or data collection.

The word “statistic” comes from the 18th century German word Statistik, which meant the “analysis of data about the state.” For governments, data collection is of special value.

The first known instance of a government collecting data of its citizens dates back to Babylon in about 3,800 BC. Governments needed to know how many people there were so they could calculate how much food was needed to feed them. A basic and necessary calculation.

There is a book in the Bible called the Book of Numbers, where God instructed Moses in the wilderness of Sinai to count those who were able to fight. The best-known biblical example is when Mary and Joseph traveled to Bethlehem to be counted and that’s why Jesus was born there.

The Roman Empire gave power to a censor who was responsible for maintaining the census, such as overseeing government finances and supervising public morality.

It was King Henry V of England who in 1414 implemented the first “passports” for those traveling on the king’s business to foreign countries.

The Metropolitan Police Act 1829 recognized the need for police to gather records so that files could be kept on individuals, identified numerically.

By 1849, the Netherlands had developed the first decentralized personal number (PN) system. And by 1936, the United States was issuing the first Social Security cards.

From the mid 1800s onwards photo and fingerprinting identification became important within the identification system as well.

It was around 1977 that all of this information started being fed into computers. And that’s when this obsession with identification really took off. Computers made it possible to collect and store masses of information on people.

In 2004, the U.S. deployed its first statewide automated palm print databases, used mainly by the FBI to catch offenders.

In 2010, Aadhaar, the world’s largest biometric digital ID system debuted in India.

The system “captures people’s fingerprints and/or iris scans and assigns a unique 12-digit Aadhaar number. As of 2019, almost 1.2 billion people had voluntarily enrolled in the program, which is intended to simplify and speed up verification for government programs while also reducing fraud.”

Biometric verification “hit the consumer market in 2013 when Apple included a fingerprint sensor in the iPhone 5S. Other smartphone manufacturers have followed suit. Apple Touch ID was later supplemented with Face ID in the iPhone X in 2017.”

The computer was supposed to make our lives easier, more convenient. We would no longer be drowning in paperwork. Each person would be easily identifiable. This has been anything but the case.

How many ways are we now required to prove who we are? Whereas once it was our physical selves, simply our height and weight, the color of our eyes, the fact that we were known in the village of our birth, that was it. People weren’t having “identity crises.” People weren’t obsessed with categorizing themselves in a hundred different ways, or listing their pronouns, or validating their existence by the number of likes they got on social media.

That is what is happening to us now. This obsession with proving identity is like a snowball rolling down a mountain, building in size and speed with no way of stopping. Every way that the government can possibly identify citizens and take their data is now being implemented, and it is still never enough. Speech recognition, iris recognition, facial recognition, DNA sequencing, hand geometry, and vascular pattern recognition, which relies on blood vessel patterns in the hands, even monitoring each person’s unique heartbeat.

Sometimes I wonder if the “mentally ill” wandering the streets and talking to themselves have really tapped into all that information floating around. Where is all that information? Where does it go? Is it trapped in some other dimension that we don’t understand? Maybe that massive build-up of endless chatter about everything and nothing breaks through somehow and into the consciousness of those who hear voices—just bits and pieces of it. It would be difficult not to go crazy under those circumstance. We’re all being turned a little (or maybe a lot) crazy by this weight of information being sucked out of us, fed into the Vast Machine where calculations are made, and then regurgitated back into our brains and our bodies. Used not just to collect information as was once the case, but to control us with that information.

All of this information is up for grabs and people in positions of power are in competition to see who can gather the most of it.

They can find out what you like to do in your spare time, your weaknesses and your strengths, if you own a dog, every country you’ve traveled to and when, if you are sensitive, sweet, angry, on the edge of violence. They can calculate if you are religious, a liar, a hypocrite, if you are a spreader of mis or disinformation, an insurrectionist. Do you display your pronouns, how many medications do you take, are you a drug addict? The list is endless.

It all started so simply. Just a way to count how many people lived in a certain place, or to prove ownership of land, or that you traveled on the king’s business.

Now, instead of you being the ultimate proof of who you are, there are a hundred different ways you’re being identified by the Vast Machine and if you get out of sync with that machine, you are in trouble. There isn’t even a person behind a desk anymore that you can go to, look into their eyes, and yell in frustration, “Look, here I am, this is me!”

If you cease to exist in the Vast Machine, you cease to exist outside of it. It is nearly impossible to escape the Vast Machine that is absorbing us into it. Every bit of our being. It is as if it has taken our obsession with identity upon itself. It insists that we prove who we are, over and over, and the more we do, the less satisfied it seems to be.

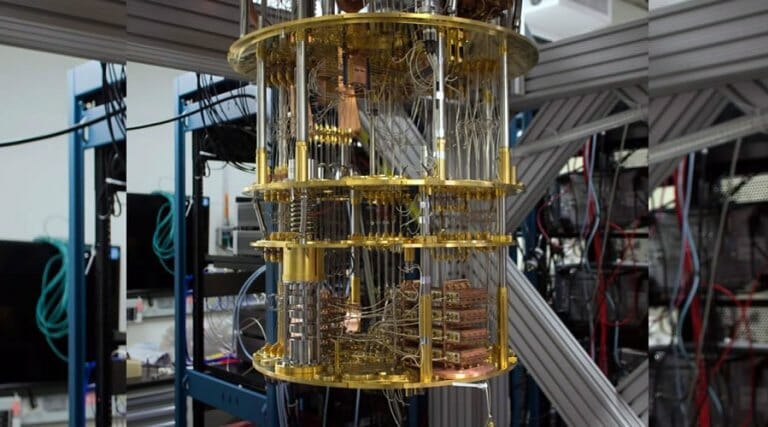

Google has created a quantum computer that they claim “was able to perform a calculation in three minutes and 20 seconds that would take today’s most advanced classical computer, known as Summit, approximately 10,000 years.’

Of course, at this point, it’s only able to perform that one specific calculation, meaning we’re still a few years from quantum computing taking over the world.”

A few years? That’s not very long. It sounds concerning. So why do we keep doing this?

Digital computers will soon reach the limits of demanding technologies such as AI. Consider just the impact of these two projections: by 2025 driverless cars alone may produce as much data as exists in the entire world today; fully digitizing every cell in the human body would exceed ten times all of the data stored globally today. In these and many more cases we need to find ways to deal with unprecedented amounts of data and complexity. Enter quantum computing.

But, why? Why is this necessary?

I don’t think we comprehend what is driving this insatiable obsession with collecting every single bit of data stored in billions of humans’ minds, every single intimate detail from sexual habits to favorite TV shows, from the poorest child begging for food on the streets of Mumbai to the richest teenager in Beverly Hills, whining to his mom that he has to have the latest I-phone or he’s literally going to die.

It can’t just be about making us buy more stuff or about billionaires’ egos as they race to see who can “rule the world.”

There’s got to be more to it than that.

For all the ways we have learned to gather information, for all the machines we have built to help us organize and calculate it and use it to control the populace, the further that control seems to be slipping through our fingers. Of course, those at the top will never admit it. They think they just need to make a few more adjustments.

Microsoft is sure they can “get it right.” To that end they are funding ID2020

It’s exciting to imagine a world where safe and secure IDs are possible.

They justify their digital ID by telling us that “the ability to prove who you are is a fundamental and universal human right. Because we live in a digital era, we need a trusted and reliable way to do that both in the physical world and online.

If it is my inherent right, why does Microsoft have to give it to me? What they are really doing is taking it away from me.

The Covid crisis was the ultimate justification for the gathering of more and more data under the guise of health and safety. To that end, Microsoft built a team of global partners. Here are four of them:

GAVI: The Vaccine Alliance. Founded and funded by The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to the tune of US$ 4.1 billion to date.

Accenture. Dealing in cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, sustainability. It is no surprise to find that Accenture’s top 3 funders are Vanguard Group, BlackRock and State Street Corportation.

The Rockefeller Foundation. Working to “boost vaccination rates and improve global health equity, The Rockefeller Foundation is working with in-country partners to gain knowledge, share insights, and create more demand for vaccines in communities with low vaccination rates.”

And the Big One, Microsoft. A The Intercept article exposes “The Microsoft Police State”:

Microsoft’s links to law enforcement agencies have been obscured by the company…. Microsoft has partnered with scores of police surveillance vendors who run their products on a “Government Cloud” supplied by the company’s Azure division and that it is pushing platforms to wire police field operations, including drones, robots, and other devices.

In the wake of 9/11, Microsoft made major contributions to centralized intelligence centers for law enforcement agencies.

By 2016, the system had ingested 2 billion license plate images from ALPR cameras (3 million reads per day, archived for five years), 15 million complaints, more than 33 billion public records, over 9,000 NYPD and privately operated camera feeds, videos from 20,000-plus body cameras, and more. To make sense of it all, analytics algorithms pick out relevant data, including for predictive policing.

Microsoft owns patent WO2020060606 – A CRYPTOCURRENCY SYSTEM USING BODY ACTIVITY DATA

ICC, Mastercard, IBM join ID2020 Good Health Pass initiative

ID2020 launched the Good Health Pass Collaborative to encourage interoperability between the COVID-19 health credentialing solutions being developed by numerous organizations.

Members of the new initiative include the Airports Council International (ACI), Hyperledger, COVID-19 Credentials Initiative, International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), Mastercard and numerous others.

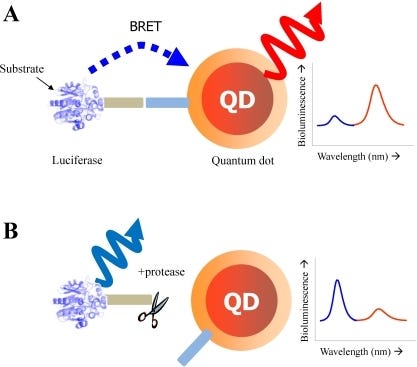

MIT researchers have now developed a novel way to record a patient’s vaccination history: storing the data in a pattern of dye, invisible to the naked eye, that is delivered under the skin at the same time as the vaccine.

“It’s possible someday that this ‘invisible’ approach could create new possibilities for data storage, biosensing, and vaccine applications that could improve how medical care is provided, particularly in the developing world,” Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor at MIT, says.

The research was—of course—funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, as well as the Koch Institute.

It all started, a long time ago, with symbols and markings on our skin. And here we are, back again, doing the same thing. Are we really advancing or are we actually returning full circle to where we were at the beginning. Back to proving our identities by cutting into our skin in order to identify who we are with numbers and symbols.

I’ve been watching The Prisoner again. I remember watching it as a child. It was strange and compelling. I didn’t understand it. I now read with a chuckle that McGoohan made it for a “small audience—intelligent people.”

The last episode of the show is exactly the same as the first. Six cannot be freed from captivity. He must continually fight against unknown forces that seek to unlock his deepest secrets and steal his stories, all while trying to turn him into an obedient, empty shell.

McGoohan said the final scene is meant to show how “freedom is a myth.” There is no conclusion to the series because “we continue to be prisoners.”

Who put us in this prison? Is it some outside force or is it ourselves?

Note: I use the term the Vast Machine often in my writing, thanks to one of my favorite authors Jonathan Twelve Hawks and his book, The Traveler.