Will anonymous transactions and the freedom they bestow be obliterated in favor of fully programmable, traceable, and expirable Central Bank Digital Currencies? perspective

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is launching a central bank digital currency (CBDC) pilot program and is exploring different use cases, such as programmability and setting expiry dates.

“CBDCs have the possibility of programming the money by tying the end use […] tokens may have an expiry date, by which they would need to be spent, thus ensuring consumption” — Reserve Bank of India, Concept Note on CBDC, October 2022

In its October “Concept Note on Central Bank Digital Currency,” India’s central bank announced that it “will soon commence limited pilot launches of e₹ for specific use cases.”

According to the RBI, “CBDCs have the possibility of programming the money by tying the end use.”

When it comes to retail transactions, CBDC “tokens may have an expiry date, by which they would need to be spent, thus ensuring consumption.”

With respect to CBDC programmability, International Monetary Fund (IMF) deputy managing director and former People’s Bank of China deputy governor Bo Li said earlier this month, “CBDC can allow government agencies and private sector players to program — to create smart contracts — to allow targeted policy functions. For example, welfare payment; for example, consumption coupons; for example, food stamps.

“By programming CBDC, those [sic] money can be precisely targeted for what kind of people can own and what kind of use this money can be utilized,” he added.

“By programming CBDC, money can be precisely targeted for what kind of people can own and what kind of use this money can be utilized” — Bo Li, IMF, October 2022

“CBDC would need to be compliant with AML [Anti-Money Laundering] regulations, which rules out truly anonymous payments” — Reserve Bank of India, Concept Note on CBDC, October 2022

On the issue of anonymity, India’s central bank said that a digital rupee would have to comply with Anti-Money Laundering (AML) regulations, “which rules out truly anonymous payments.”

The idea is that complete anonymity “poses a policy trade-off—the more anonymous, the larger the risk for illicit use.”

According to the report, “Most central banks and other observers have noted that the potential for anonymous digital currency to facilitate shadow-economy and illegal transactions makes it highly unlikely that any CBDC would be designed to fully match the levels of anonymity and privacy currently available with physical cash.”

Therefore, “Considering the potential risks associated with privacy and anonymity, the idea of complete anonymity in digital world is a misnomer.”

“Individuals could be allotted a certain amount of ‘anonymity vouchers’ that could be used for small transactions, with larger transactions still visible to financial intermediaries and the authorities” — Reserve Bank of India, Concept Note on CBDC, October 2022

Ruling out the option for complete anonymity, India’s central bank is looking to the European concept model for a programmable CBDC, “by which individuals could be allotted a certain amount of ‘anonymity vouchers’ that could be used for small transactions, with larger transactions still visible to financial intermediaries and the authorities.”

In other words, there would be “anonymity for small value and traceable for high value.”

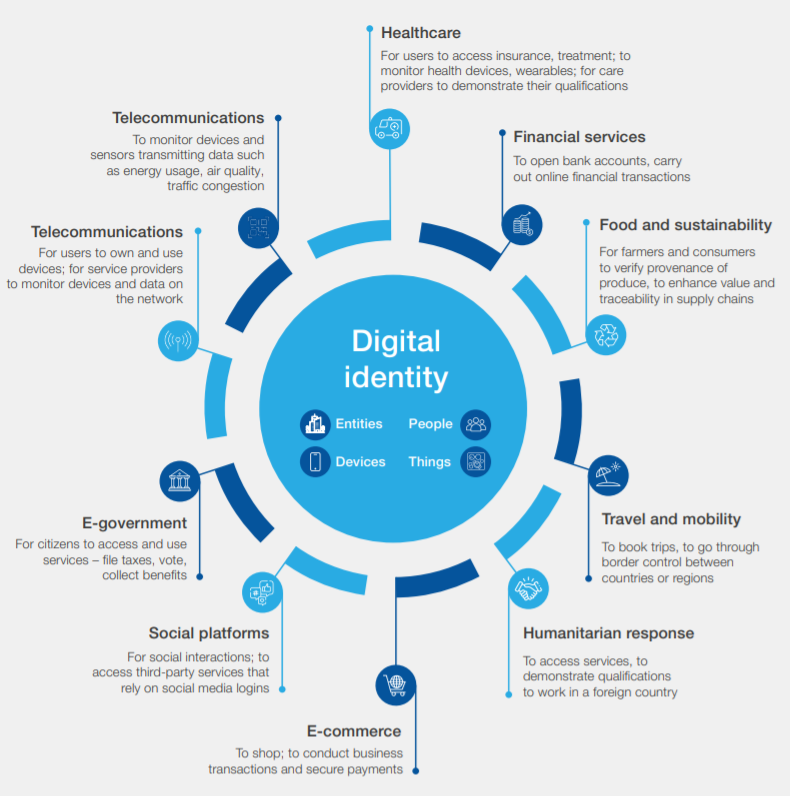

Eliminating complete anonymity also means that a CBDC would have to be identity verified.

The RBI report states that “the identity of CBDC users would need to be known to at least some authority or institution in the wider CBDC network who can validate the legitimacy of their transaction.”

Similarly, the heads of both the American Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank recently confirmed that their respective digital dollars and digital euros, should they go forward, would not be anonymous as well.

In the absence of complete anonymity, some form of digital identity would be required.

“This digital identity determines what products, services and information we can access – or, conversely, what is closed off to us” — World Economic Forum, 2018

“The Tribune ‘purchased’ a service being offered by anonymous sellers over WhatsApp that provided unrestricted access to details for any of the more than 1 billion Aadhaar numbers created in India thus far” — The Tribune, January 2018

India already has a digital identity framework in place through its Aadhaar system, which is administered by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI).

According to the UIDAI, a person willing to enroll in Aadhaar “has to provide minimal demographic along with biometric information.”

In January, 2018, The Tribune revealed that in just 10 minutes the India-based newspaper was able to purchase “unrestricted access to details for any of the more than 1 billion Aadhaar numbers created in India.”

“The Aadhaar number in India — that single identifier is able to track your activity across all facets of your life, from employment, to healthcare, to school, to pretty much everything you do” — Elizabeth Renieris, Congressional Testimony, July 2021

During a hearing on digital identity in the US House of Representatives in July, 2021, Notre-Dame-IBM Technology Ethics Lab Founding Director Elizabeth Renieris testified that India’s digital identity scheme was poorly done.

“What we’ve seen with digital ID schemes gone wrong is that they’ve basically used a single identifier,” said Renieris.

“For example, the Aadhaar number in India — that single identifier is able to track your activity across all facets of your life, from employment, to healthcare, to school, to pretty much everything you do […] You can’t have this kind of contextualized personal identity.”

“It’s also problematic from the standpoint of data security. If you compromise your number, you have concerns around that,” she added.

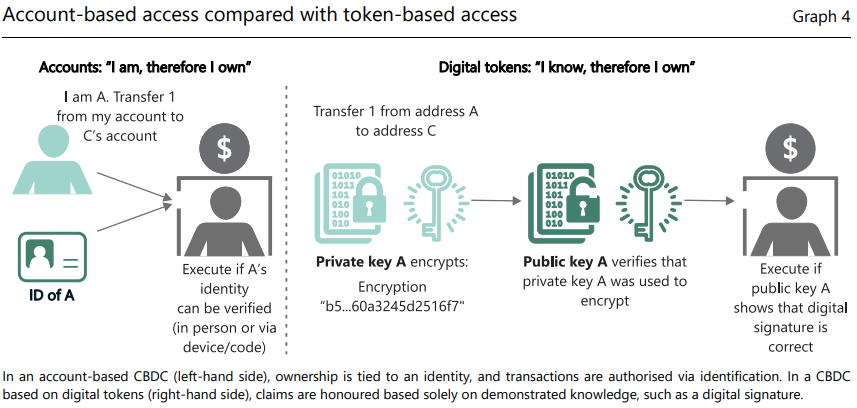

“CBDC can be structured as ‘token’ or ‘account’ based or a combination of both” — Reserve Bank of India, Concept Note on CBDC, October 2022

Source: Bank for International SettlementsThe RBI concept note on CBDC attempts to explain the objectives, choices, benefits and risks of issuing a CBDC in India, which can be structured as either “token” or “account” based, or a combination of both.

In an account-based CBDC system, “during the initial creation of each CBDC account, the identity of the account holder would need to be verified.”

In a token-based system, “the entire chain of ownership of every token must be stored in an encrypted ledger.”

For retail transactions, the concept note outlined how the RBI preferred a token-based digital rupee “with an ability to include programmable feature that supports efficiency such as standardization of compliance rules, fraud detection.”

For wholesale interbank settlements, India’s central bank is considering an account-based digital rupee.

“A token-based CBDC is viewed as a preferred mode for CBDC-R [retail] as it would be closer to physical cash, while account-based CBDC may be considered for CBDC-W [wholesale].”

“CBDC is aimed to complement, rather than replace, current forms of money and is envisaged to provide an additional payment avenue to users, not to replace the existing payment systems” — Reserve Bank of India, Concept Note on CBDC, October 2022

The RBI claims that “CBDC is aimed to complement, rather than replace, current forms of money and is envisaged to provide an additional payment avenue to users, not to replace the existing payment systems.”

However, a World Economic Forum Agenda blog post from September, 2017 lists the “gradual obsolescence of paper currency” as being “characteristic of a well-designed CBDC.”

If and when India, or any country for that matter, moves forward and issues their CBDC, will there ever be a chance of going back to physical cash?

Will the benefits outweigh the risks?

Or will anonymous transactions, and the freedom they bestow, be obliterated in favor of fully programmable, traceable, and expirable Central Bank Digital Currencies?

The Sociable editor Tim Hinchliffe covers tech and society, with perspectives on public and private policies proposed by governments, unelected globalists, think tanks, big tech companies, defense departments, and intelligence agencies. Previously, Tim was a reporter for the Ghanaian Chronicle in West Africa and an editor at Colombia Reports in South America. These days, he is only responsible for articles he writes and publishes in his own name. tim@sociable.co