In May of this year Labour MP and Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham described Universal Basic Income as “An idea whose time has come”. Is he right? Is it an idea that has been bubbling away below the surface and has risen to the top.

The ‘time has come’ for a Universal Basic Income says Andy Burnham

Well, judging by the data he is partly right. It is an idea that has become increasingly popular in recent years. Popular enough that many think-tanks are promoting it, political parties are making pledges about it, and NGO’s and governments are trialling it.

Whether or not it is practicable or will become government policy is however another matter and beyond the scope of this article, all that can be said is a popular idea amongst those in power and those who influence them and is becoming more so with each passing week.

The current seed of and enthusiasm for UBI could be said to have emerged from various European academics in the late 1970s’s and 1980’s.

In the Netherlands several academics published works that influenced one Dutch political party (Politieke Partij Radicalen) so much so that it included an unconditional basic income promise in its electoral program in 1977.

France, England, Denmark, Germany, and later France followed a similar path to the Netherlands, but for various reasons the idea of UBI failed to make it to the level of mainstream politics.

The cognitive seeds of basic income however had been sown in the minds of many, and the basic principles were being explored. One of these being whether the basic income should be truly universal, i.e., a ‘Universal Basic Income’, or means tested subsides i.e., a ‘Guaranteed Minimum Income’.

The former, UBI, is a simpler process that largely involves given a fixed sum of money to all members of society regardless of their pre-existing income levels.

The latter, GBI, targets particular groups who have low-income levels or have been determined to be disenfranchised in some way (such as homeless, young, or BAME individuals), and boosts their income level to a certain extent.

(While these two approaches are very different to one another and use different terminology to define them, news publications have used the term UBI to describe a trial or pilot that is a GBI, which is not only inaccurate and misleading it also muddies the water and may confuse readers. Hence this is something to bear in mind when reading news articles about ‘Universal Basic Income’, because they may be referring to UBI or some other Basic Income idea.)

Since the turn of the century the idea of UBI has become more popular and accepted throughout mainstream politics. This can be evidenced by the fact that high profile politicians like Andrew Yang, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Tulsi Gabbard in the USA, and Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell in the UK have spoken out in favour of UBI.

There have also been several basic income trials where the basic principles have been tried, the most well-known being the Finnish experiment which went on for two years and involved thousands of participants.

The results of the pilot were mixed, with some calling it an abject failure due to the failure to boost employment, while others looked at the benefits to mental health and wellbeing. The lack of conclusive evidence in favour of basic income has not deterred its advocates.

That was the situation from the 1970s up until recent years, but where do we stand now in 2022? Is UBI a popular topic for debate or has it faded back into obscurity?

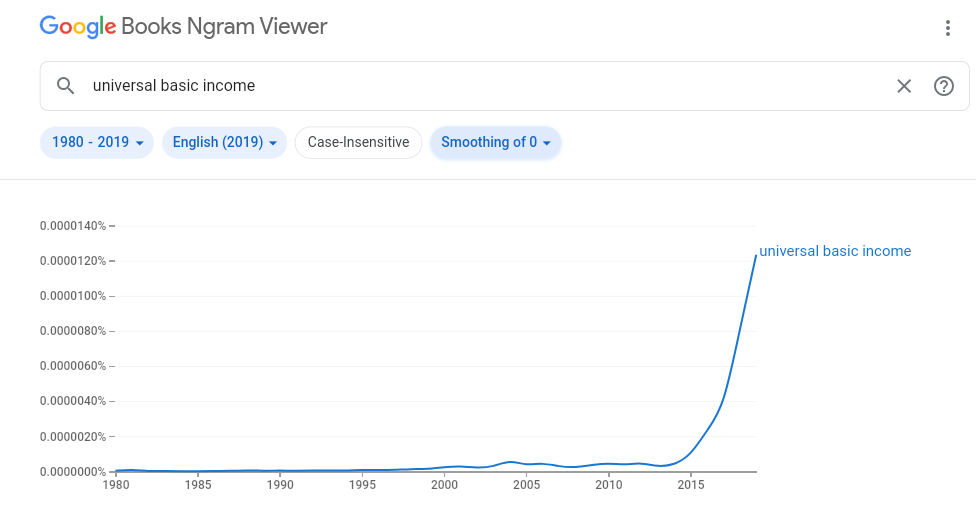

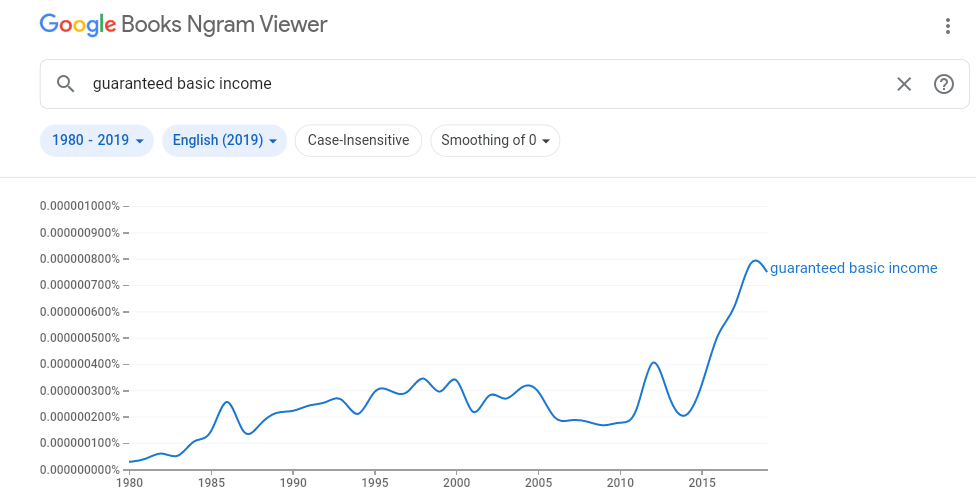

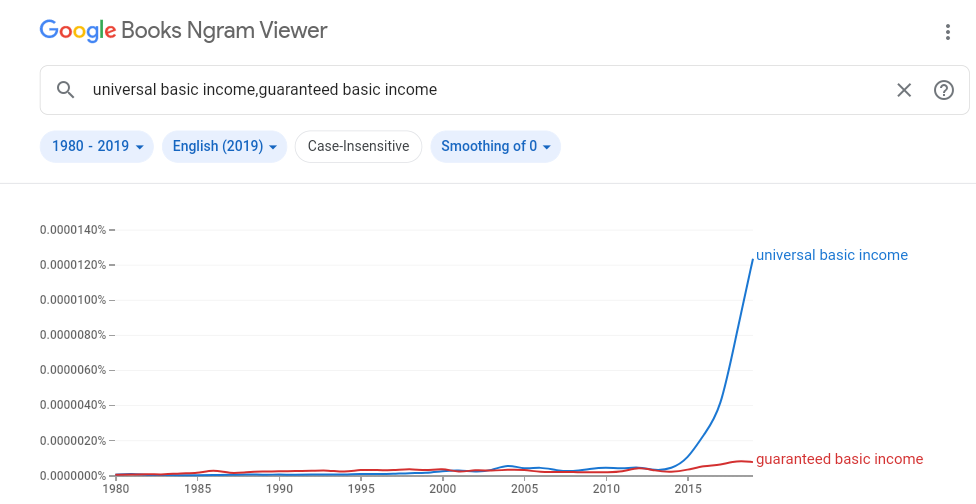

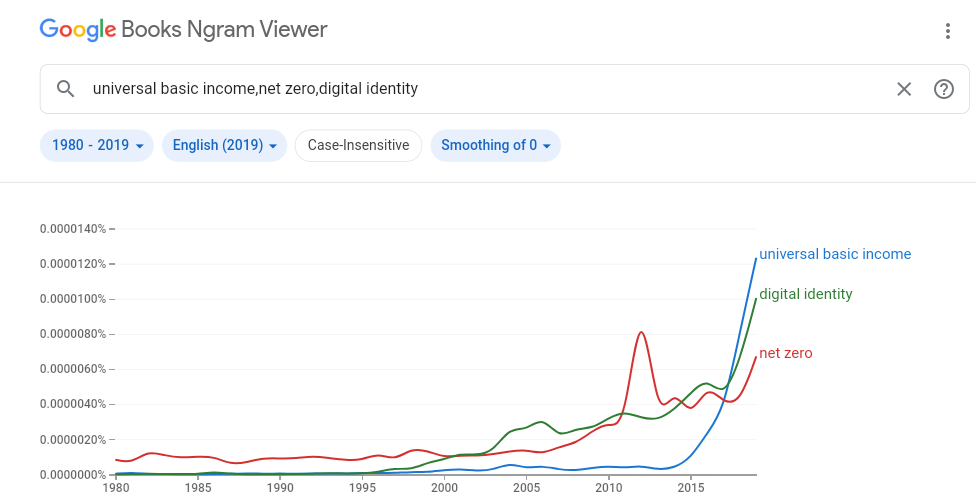

One metric for determining how popular a word, or string of words, is over a given period within a given medium (e.g., print, or television news) we can use an Ngram Viewer, such as Google Ngram Viewer. Google Ngram Viewer “charts the frequencies of any set of search strings using a yearly count of n-grams found in sources printed between 1500 and 2019“.

When we use Google Ngram Viewer and the string of words “universal basic income” we can see that there is a general upward trend from 1980 up until 2019 (the most recent date that n-gram allows), but the term become increasingly common from the mid-2010s onwards.

To provide some sort of context for the popularity of these terms a graph with keywords for two other topical issues (net zero and digital identity) has been included. As can be seen, while these two other issues have a similar upward trend to ‘universal basic income’ they are clearly not as frequently written about.

The related basic income idea “guaranteed basic income” also has a similar upward curve to “universal basic income”, although it also has been increasing since 1980, so considerably longer than Universal Basic Income.

Without further investigation it would be hard to explain why UBI has overtaken GBI in terms of popularity. It could be due to changing use of terminology amongst academics, or it could be due to the changing popularity of certain ideas, or any number of other factors.

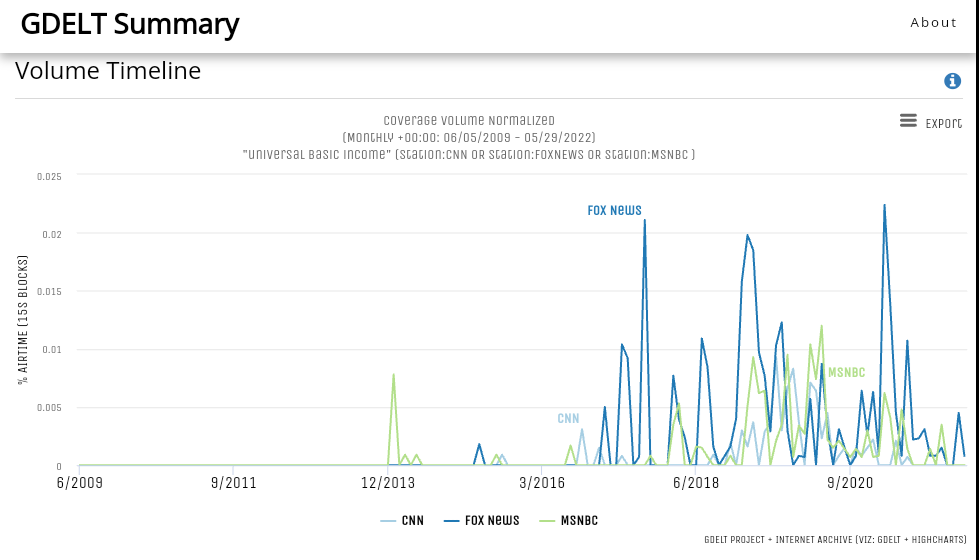

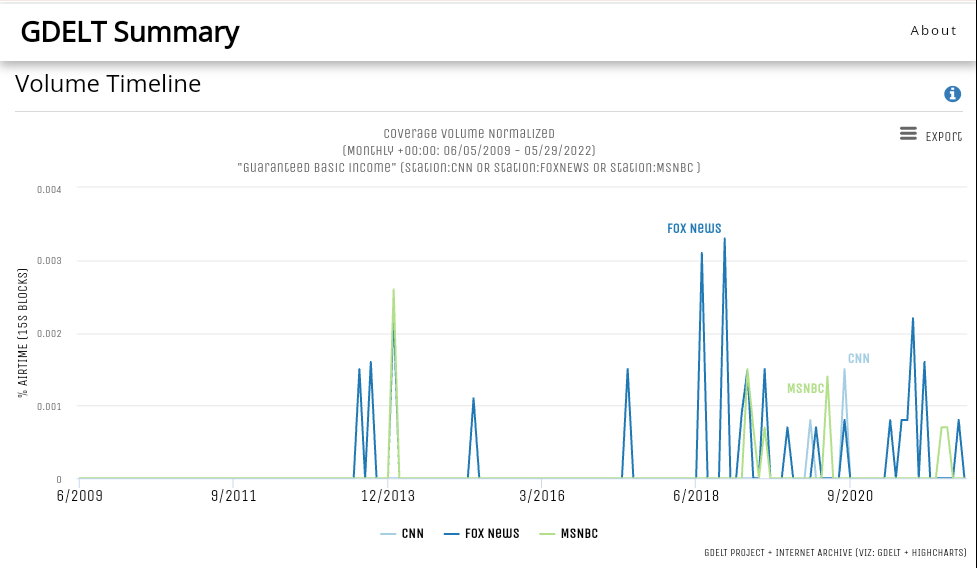

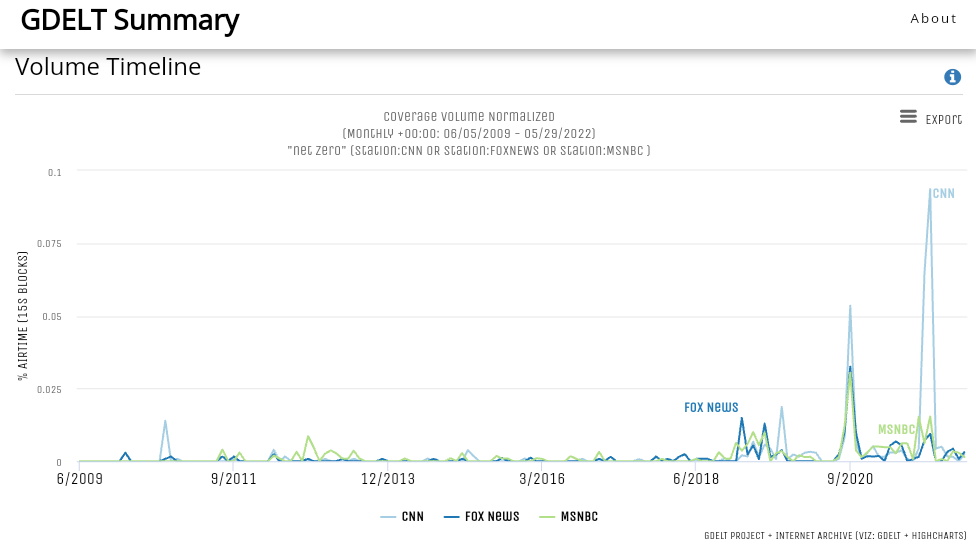

What we can say with confidence is that UBI is an increasingly popular idea amongst academics and other writers, but not only writers because mainstream television news channels in the USA are also reporting more frequently on UBI, as can be seen in the graphs below which use a similar method to Google Ngram Viewer to chart how frequently a word or string of words appears on given television channels.

The webpage describes the graphs as following: “Results timelines report the percent of 15 second clips monitored from a station in a given day that contained your keyword”.

The keywords in this case for the three graphs being ‘universal basic income’ ‘guaranteed basic income’ and ‘net zero’.

A downside of this software compared to Google Ngram Viewer is that it does not easily allow for the comparison of different keywords on the same graph.

This means that while we can see the long-term trends, i.e., increasing or decreasing frequency of use, we cannot compare keywords with one another to see how popular a given keyword is relative to another.

The key point when looking at these graphs is not the amount of time that is given to the topic of UBI, but rather the long-term trend which can be seen to increase considerably from the mid-2010’s onwards, which mirrors what we saw with the Google N-gram Viewer graphs.

While these graphs do not show data back to 1980, they do show data from 2009 to the present day, and as can be seen there is a massive increase in the frequency of the term “universal basic income” from the mid-2010’s onwards.

Obviously this mirrors what we have seen in the Google Ngram Viewer graphs which means that not only is the idea of UBI being talked about and discussed within the written literature it is being broadcast and discussed in mainstream media indicating how important it has become as a concept, and quite possibly, how much it is being promoted and normalised as an idea by academics and numerous high profile individuals including politicians, religious figures and so on.

Here in the UK, Andy Burnham is one of those high-profile individuals who has been speaking out in praise of UBI recently describing it as ‘an idea whose time has come’ during a visit to a school in Wigan.

This is the second time in recent years that he has praised UBI, the first being in 2020 on BBC Radio 4 when he suggested that it be used to help the economy recover once the lockdown had been lifted.

Another high profile to endorse is Pope Francis, who, in 2020 said that a ‘universal basic wage’ “would ensure and concretely achieve the ideal, at once so human and so Christian, of no worker without rights”.

It is incidents like this that introduce the idea of UBI to a wider audience than it may otherwise have, as well as generally promoting it and painting it in a positive light.

An added long-term benefit of normalising Universal Basic Income in this way for proponents of it is that when the time comes to make UBI, or some variant of it, government policy people will be more aware of it and thus amenable to it.

However, before that happens and UBI becomes government policy it first needs to become a party-political position, and that is most definitely happening.

Three of the main political parties in England have declared that they are in favour of UBI in some form or another. The Liberal Democrats, Greens and Labour have all spoken positively of UBI. The Greens going as far as to make a pledge to introduce UBI by 2025.

The Conservatives, on the other hand, have stated that they are not in favour of UBI, as can be seen in the responses to two written parliamentary questions on the subject. And the fact that these questions were asked over a two-year period and their position has not changed indicates that they will remain firmly opposed to UBI, at least for the foreseeable future.

The Conservative’s position on UBI is unsurprisingly reflected in the attitude of the Conservative-leaning Think Tanks, such as The Centre for Policy Research which has openly come out against UBI.

If think-tanks, that provide policy advice to political parties, do not come out in favour of a given idea then it is reasonable to assume that their corresponding political party is opposed to it as well.

Some other centre-right, or right leaning, think-tanks like Adam Smith Institute however are in favour of UBI, one of their reports saying, “The analysis suggest that the UBI is politically feasible, socially desirable and financially sustainable”.

The Institute for Economic Affairs while not favourable towards UBI are not hostile towards it either, as can be seen in one paper: “There is a pressing need for those who are sceptical of both UBI and UBS to come up with not only criticisms and objections but their own ideas for reform, however radical”.

As for other Think-Tanks, several of the more prominent ones have spoken out in favour of UBI or one of the basic income variants. Unsurprisingly some of them are left leaning, such as IPPR.

Despite their respective positions they are discussing and exploring the idea which feeds the general debate about the topic and helps to keep it alive, as was seen in the Google Ngram Viewer graph earlier in this article, and the debate about UBI is very much alive.

Without this debate it would be nigh on impossible to generate the political interest to run UBI pilots or trials. Pilots that are essential to national governments so they can collect data and determine whether it would be possible to implement such policies on a national scale, which two devolved governments in the UK are contemplating.

The Welsh Government announced in February that it will run a basic income pilot for care leavers. The governments website explaining that: “All young people leaving care who turn 18 during a 12-month period, across all local authority areas, will be offered the opportunity to take part in this pilot. The pilot will begin during the next financial year, and we anticipate over 500 young people will be eligible to join the scheme.”

The pilot will run for a minimum of three years with each member of the cohort receiving a basic income payment of £1600 per month for a duration of 24 months from the month after their 18th birthday.

The Scottish government has also shown its desire to run a basic income pilot.

In addition to these two trials by devolved governments in the UK, other national governments around the world are increasingly talking about running UBI or GBI trials. Ireland is in the process of getting ready to begin its basic income trial for 2,000 artists. The application process has just finished. 9,000 people applied to be part of the trial. Each successful applicant will receive 325 euros per week over a three-year period.

In Poland, a team of researchers is preparing to launch a pilot programme to test the impact of Universal Basic Income. The experiment is a joint venture between academics and local government.

The programme could see between 5000 and 31000 participants each receiving monthly payments of 1,300 zloty (280 euros).

In India, a report commissioned by the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister propounded that the government of India should roll out a universal basic income scheme to reduce sharp income gaps.

Over in the USA there are multiple basic income pilots either being considered or are getting underway. One such pilot is happening in Illinois where on the 18th May Cook County officials announced plans for a $42 million guaranteed income program, the nation’s largest publicly funded cash pilot. It will pay $500 per month to 3,250 who meet certain financial criteria (very low income) for a period of two years.

While governments could be said to be leading the way with basic income pilots there are indeed attempts by the private sector too. In Switzerland a crypto-based basic income project is trying to get off the ground.

The trials and pilots listed above are just the tip of the iceberg. There are many more pilots in various stage of development, and no doubt more will come in due course because, as we have seen, basic income is an idea that is growing in popularity amongst academics, political parties, think tanks, governments and others, many of whom wish to make it a reality as they believe, like Andy Burnham, that Universal Basic Income is “an idea whose time has come”.