To believe and perpetrate the “Good War” and “Greatest Generation” myths, we must ignore many sordid realities. I’ve written about some of them here, here, and here (and several other posts).

This time, I’ll focus on the memory-holed topic of AWOL American soldiers running wild in Europe.

“Paris was full of them,” remarks historian Michael C.C. Adams.

Journalist Chet Antonine has written of U.S. troops “looting the German city of Jena where the famous Zeiss company made the best cameras in the world.”

The U.S. compiled a list of “Continental AWOLs” that included as many as 50,000 men. Many of them turned to the black market.

“Allied soldiers [in Italy] stole from the populace and the government, and once, GIs stole a trainload of sugar, complete with the engine,” writes Adams.

V.S. Pritchett, in the New Statesman and Nation (April 7, 1945), wrote about GIs stealing cameras, motorbikes, wine glasses, and books.

In the New York Herald Tribune, the legendary John Steinbeck reported on three soldiers arrested for selling stolen watches.

In October 1945 alone, American GIs sent home $5,470,777 more than they were paid.

One illegal form of currency for GIs — AWOL or otherwise — was whiskey. As alcohol dependency rose, desperate soldiers resorted to such homegrown brews as Aqua Velva and grapefruit juice or medical alcohol blended with torpedo fluid.

The buying and trading weren’t limited to moonshine. Throughout the European theater of operations, the Allied soldiers did their best to exploit desperate and vulnerable females.

“In a ruined world where a pack of cigarettes sold for $100 American, GIs were millionaires,” says Antonine. “A candy bar bought sex from nearly any starving German girl.”

“Soldiers had sex, wherever and whenever possible,” Adams reports. “Seventy-five percent of GIs overseas, whether married or not, admitted to having intercourse. Unchanneled sexual need produced rape, occasionally even murder. Away from home, where nobody knew them, some GIs forced themselves on women.”

In northern Europe, venereal diseases caused more U.S. casualties than the German V-2 rocket. In France, the VD rate rose 600 percent after the liberation of Paris.

Where did those 50,000 AWOL GIs go after doing their part to soil the image of a “good” war? Nearly three thousand were court-martialed and one was executed, Private Eddie Slovik of G Company, 109th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division. The Detroit native deserted in August 1944, surrendered in October of that same year and was put on trial a month later.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the execution order of December 23, 1944, and Slovik faced a twelve-man firing squad at St. Marie aux Mines in eastern France shortly thereafter. None of the eleven bullets (one is always a blank) struck the intended target — Slovik’s heart —and it was a full three minutes before he died. Outrage spread quickly and there were no further executions.

As for the rest of the AWOL GIs, Antonine’s guess seems as good as any: “A goodly number of them undoubtedly stayed on in Europe as they had after World War One. Perhaps some of them got bogged down in ordinary life, marrying and having children. Others may have continued their lives of crime and ended up in prison. Only nine thousand of them had been found by 1948.”

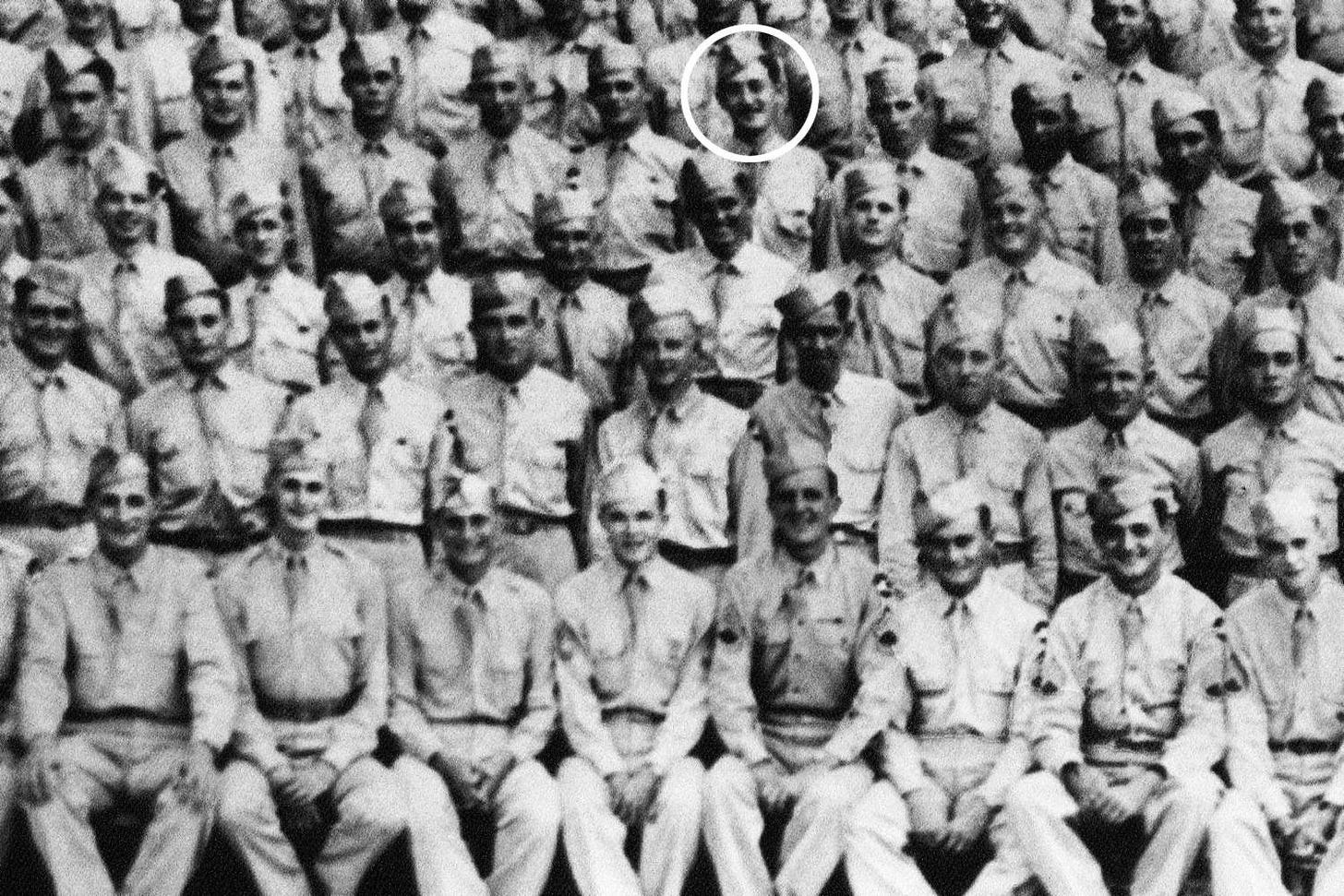

Then there was a certain staff sergeant who used his authority to anoint himself the absolute lord of the German town of Bensheim during those black market days: future Nobel Peace [sic] Prize winner, Henry Kissinger.

“After evicting the owners from their villa,” Antonine writes, “Kissinger moved in with his German girlfriend, maid, housekeeper, and secretary and began to throw fancy parties.”

These fancy parties were not the norm in Bensheim, an area where the average German made do with fewer than 850 calories per day. FYI: That’s less food than was given to prisoners at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Seventy-eight years later, Kissinger the parasite continues to see himself as an absolute lord. Here’s something I recently wrote about him: