In this era of crushing intellectual conformism, it is always a pleasure to read about figures of the past who were not afraid to be themselves and to express a set of opinions which belonged to them and to nobody else.

Such is the case with the Anglo-French writer and poet Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953), who is the subject of a new book by Sussex historian Chris Hare.

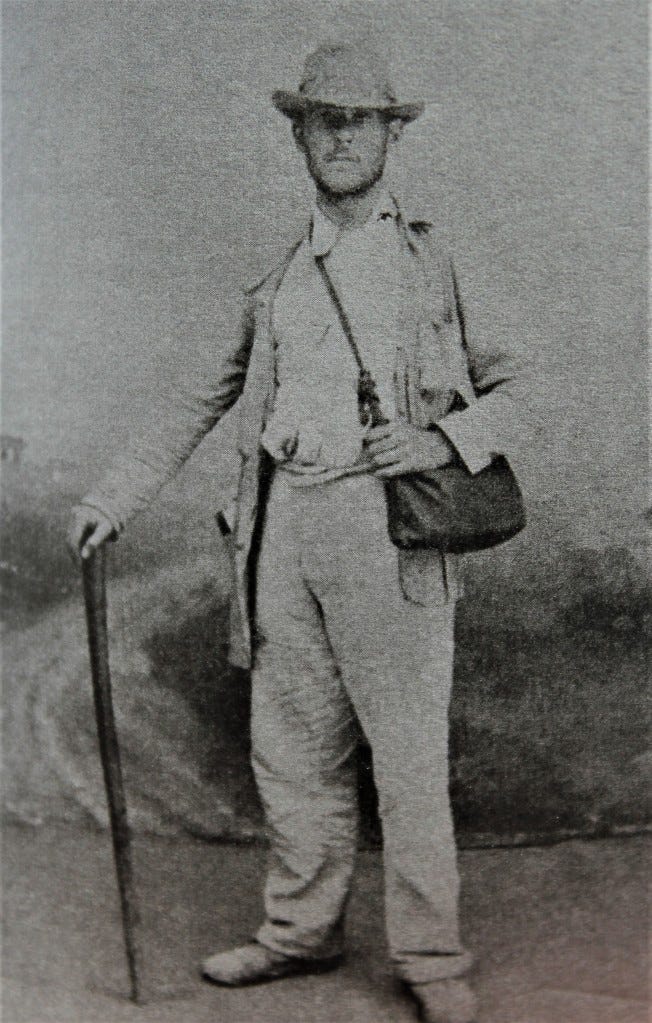

Chris (pictured below) has been a good friend of mine for some 30 years now and I know what a great inspiration Belloc has been for him and indeed for his wife Ann Feloy, who has created a successful theatrical adaptation of Belloc’s novel The Four Men.

One parallel between his own life and that of Belloc is that both initially embarked on a political career – Belloc as a Liberal Party MP and Chris as a Liberal Democrat county councillor and 1997 general election candidate – only to become seriously disillusioned with the political system.

Another connection is that, like Belloc who lost sons in both world wars, Chris and Ann have had to face up to difficult bereavement in their lives and the book is dedicated to the memory of their son Oliver, as indeed is Olly’s Future, the charity established in his name.

Hilaire Belloc: The Politics of Living, published by History People UK, does not claim to be a biography or academic evaluation, but is rather a very personal look at Belloc.

Although clearly motivated by deep affection for his subject matter, Chris does not seek to idolize him and confronts head-on several controversial aspects of Belloc’s thought, which took him into territory far away from the Cautionary Tales for Children for which he is often fondly remembered.

One thing I myself share with Belloc is the fact that his life was divided between the south of England and France – the latter being his place of birth, in fact.

I also share his longing for an old England, an old Sussex, which was already being eroded in his days and which has now pretty much disappeared, with massive new housing estates covering fields which I once traversed in order to reach village pubs now repackaged as pricey tavern-themed restaurants.

The Four Men, explains Chris, is a book dedicated to rural Sussex, where Belloc was effectively “hiding from the real England of cities and capitalism, of motor cars and advertising hoardings”. [1]

He did his best to avoid Sussex towns of “the London sort” which “had grown up with the railway and represented a dramatic interruption in the slow pace of rural life”. [2]

Belloc himself described this as the “detestable part of the county, which was not made for men, but rather for tourists or foreigners, or London people that had lost their way”. [3]

The demise of Sussex caused great sadness for the poet of Shipley, writes Chris: “In 1911, Belloc knew very well that the day might come ‘when the holy place shall perish and all the people of it’, yet he still hoped that the Sussex he knew as a child might still endure: its clear, peaceful, open downland, its indomitable people, and its continuity with ages past. By 1936, he had abandoned all hope”. [4]

This was the year in which Belloc described the destructive encroachment of what he termed “the disease of Industrial Capitalism” [5] in this haunting passage from The County of Sussex.

“Which of us could have thought, when we wandered, years ago, in the full peace of the summer weald, or through the sublime void of the high Downs, that the things upon which we had been nourished since first we could take joy in the world would be thus rapidly destroyed in our own time, dying even before we ourselves should die?

“Yet apparently it has come. In the old days when the huge amorphous mass of London, more numerous than many a state, was only linked with the sea-coast by the railway, we feared for the future but did not despair of it…

“Then came the change: London broke out like a bursting reservoir, flooding all the ways to the sea, swamping our history and our past, so that already we are hardly ourselves. Of a week-end the roads from north to south are like a city street. The new engines climb the Downs, they invade every corner. You may hear the machine-gun fire of a motor bicycle on the greensward of Chanctonbury Ring.

“There is no retreat wherein you can escape the blind inhuman mechanic clatter. How could any organism survive this ubiquitous thrusting into its substance of alien things?” [6]

Behind this lament for the murder of a living culture lay, of course, a positive belief in the importance of what I have called withness, the human belonging to a particular place.

Wrote Belloc: “If a man is part of and is rooted in one steadfast piece of earth, which has nourished him and given him his being, and if he can on his side lend it glory and do it service, it will be a friend to him forever, and he has outflanked Death in a way”. [7]

Belloc’s personal outlook often brought together positions which appear contradictory from a conventional perspective.

For instance, he managed to combine a solid attachment to the Roman Catholic faith with a pagan sensibility, writing poetry in praise of the “Holy Moon” and of sacred rivers and springs. [8]

And Belloc’s defence of tradition and dislike of industrial “progress”, stances regarded as “reactionary” by the dogmatic Left, were accompanied by an intuitive support for the broader struggle for social justice.

He was, he himself said, a socialist sympathiser “before the socialist creed had been captured”. [9]

Adds Chris: “Belloc as a young man was full of indignation about the impact that industrial capitalism was having on ordinary people, he was also outraged by the dispossessions of small farmers and the loss of common rights that had been enjoyed for centuries”. [10]

He opposed attempts to “criminalise the poor” [11] and also to restrict the drinking of alcohol by the popular classes. [12]

He supported Home Rule for Ireland and was a critic of the British Empire, describing famous Elizabethan “seadogs” like Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh as “slave-dealers and pirates, secretly supported by the powerful men of the State”. [13]

Belloc also saw clearly the pernicious role played by the corporate media of his time, writing: “The press of our great cities is controlled by a very few men, whose object is not the discussion of public affairs, still less the giving of full information to their fellow-citizens, but the piling up of private fortune”. [14]

At the same time as Belloc condemned this gathering-up of riches as an evil at odds with the tenets of his faith, [15] he vehemently denounced the Bolshevik takeover in Russia, [16] as well as state socialism in general.

Alongside his friend G.K. Chesterton, he believed in the redistribution of property as opposed to either its monopolisation or its abolition, explains Chris.

“It was a point of view that sat uncomfortably with either the socialist or the capitalist point of view and, as a result, Belloc can appear at one moment a revolutionary and, at another, a reactionary”. [17]

However, his instinctive rejection of binary either/or thinking led him to fall into the trap of ternary thinking, which is to say the assumption that because you don’t like either “a” or “b”, then “c” will probably be a good thing.

Chris writes: “Belloc could have no sympathy with Lenin or Trotsky, but neither could he reconcile himself with the capitalist system, so he was going to be attracted to a ‘third way’, between these two unpalatable options”. [18]

This led him to find merit not only in Charles Maurras and Action Française in France, but also in Benito Mussolini in Italy.

It is difficult to understand how a libertarian anti-industrial traditionalist could have been enthusiastic about an ultra-modernist authoritarian motorway-building Fascist dictatorship!

The contradictions were many and blatant. Notes Chris: “In 1926, while Mussolini is rounding up his opponents and suppressing independent trade unions, Belloc is supporting the General Strike in England”. [19]

Happily, Belloc was not similarly fooled by Nazism in Germany and “realised that its rise had been aided by the great financial institutions, who had lent the Nazi regime loans on favourable terms”. [20]

He wrote in 1939: “This German monstrosity was brought into being by the Bank of England under the orders of which our politicians also helped build up the new Germany, and now we must face the consequences”. [21]

His awareness of, and opposition to, the stifling power of finance led Belloc into choppy political waters.

The controversy started with his role in exposing the Marconi corruption scandal in the UK in the run-up to the First World War.

The fact that this involved several Jewish businessmen, alongside the claim that he once offended the House of Commons by using the term “the Anglo-Judaic plutocracy”, [22] have led some to label him anti-semitic.

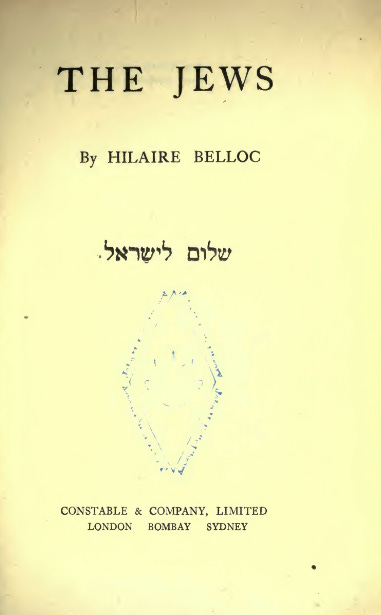

His case was perhaps not helped by the fact that he wrote a 1922 book entitled The Jews, even though it was in fact dedicated to his Jewish secretary Ruby Goldsmith and had the stated aim of warning of an approaching disaster for Jewish people if they remained closely associated in the pubic mind with both international finance and Soviet communism.

He himself did not succumb to such easy conflations, insisting: “I think people are great fools who do not appreciate what part the Jew has played in revolutionary movements, but people are much bigger fools who get it on the brain and ascribe every revolutionary movement to Jews and secret societies. The prime cause of revolution is injustice, and the protest against injustice, when it becomes violent, produces revolution”. [23]

In the preface to the 1928 second edition, Belloc wrote: “When the book first appeared it was called by those who had not read it ‘Anti-Semitic’ – that is, a book written in antagonism to Jews by a man who hated Jews. I have no antagonism of this kind. So far from hating the Jewish people, I seek their company, I enjoy their conversation, and of my friends the proportion who are either wholly or partly of Jewish blood is large”. [24]

In private correspondence, Belloc condemned “mere anti-Semitism and a mere attack on a Jew because he is a Jew” [25] and ascribed “the irritation against Jewish power in Western Europe” to “the annoyance of feeling that non-national financial power can restrict our information and affect our lives in all sorts of ways”. [26]

Chris devotes an entire chapter of his book to this thorny issue and finds that Belloc was “not a man with hatred in his heart for the Jewish people”, adding: “I would argue that Belloc’s perceived hostility towards Jews was primarily a hostility towards the banking and financial system generally, in which Jews were disproportionately represented”. [27]

Today, of course, we have reached the surreal point where merely to warn of the threat from global financial power, without the slightest reference to any Jewish involvement, is regarded by the system’s media as being “linked to antisemitism” and thus worthy of censorship.

Belloc would not have been impressed.

More information on the book can be found at historypeople.co.uk