Bankruptcy proceedings in the Canary Islands, Spain’s heavily tourism-dependent island chain, soared a whopping 276% year over year in 2022, according to the latest data published by the General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ) in its report, “The Effects of the Economic Crisis on Judicial Bodies.” The archipelago also saw the highest rate of dismissal claims in Spain, with around 400 of every 100,000 inhabitants losing their jobs.

But this trend is not unique to the Canary Islands, nor indeed Spain. It is happening across large swathes of Europe’s economies, as legions of businesses succumb to the final straw of Europe’s largely self-inflicted energy crisis.

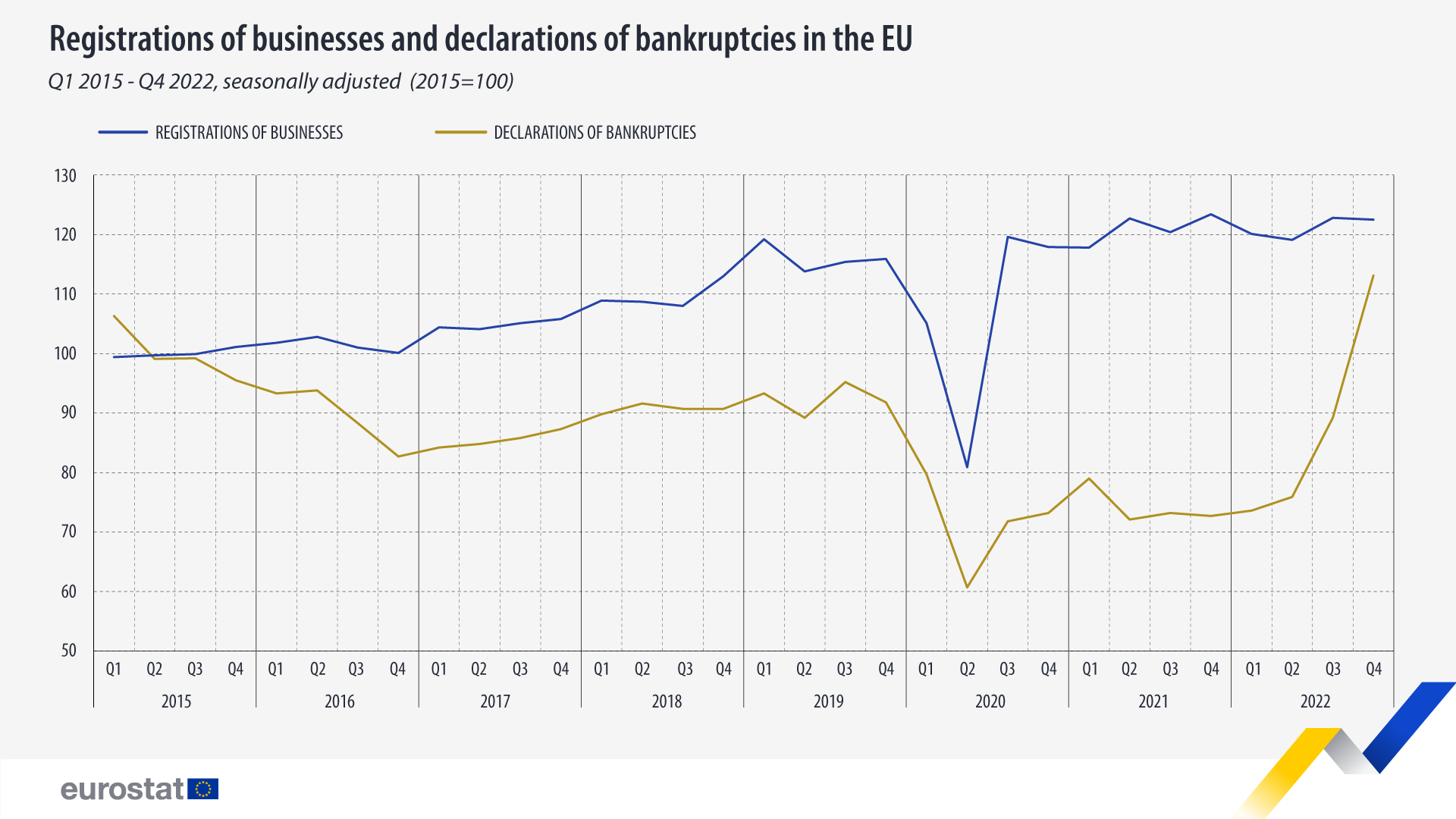

n the EU as a whole the number of bankruptcy declarations initiated by businesses increased substantially (26.8%) quarter-on-quarter in the fourth quarter of 2022, reaching the highest levels on record since Eurostat began collecting EU-wide bankruptcy data in 2015. The number of bankruptcy declarations increased during all four quarters of 2022. As the Eurostat graph below shows, at the current rate of business destruction it won’t be long before businesses are closing at a faster rate than they are opening.

This trend, of course, was not hard to foresee. In August 2022, I warned that the EU’s largely self-inflicted energy crisis and resulting inflation is tipping legions of small businesses over the edge:

After reeling from one crisis to another, Europe’s heavily indebted and deeply debilitated small businesses — the backbone of the economy — face the ultimate threat from energy shortages and soaring prices.

With the specter of stagflation looming large over Europe and the price of energy rising at a blistering pace, hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions, of small businesses face the grim prospect of closure this winter. In the UK, much of the news cycle in recent weeks has been dominated by the plight of struggling families grappling with surging energy bills. But many businesses are, if anything, in an even worse pickle, since they don’t have price caps on the energy they pay. Some business owners are facing an increase in bills of more than 350%.

Across Europe small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs), particularly in sectors like travel and tourism, culture and hospitality, have borne much of the brunt of the economic fallout of the pandemic. The stimulus packages — including furlough programs, debt moratoriums and low-interest emergency loans — helped to tide over many (but not all) of the worst-hit businesses but that support has ended. Meanwhile many of the economic problems spawned by the pandemic, including supply chain bottlenecks and labor shortages, continue to linger. Energy shortages and surging prices are likely to be the final straw.

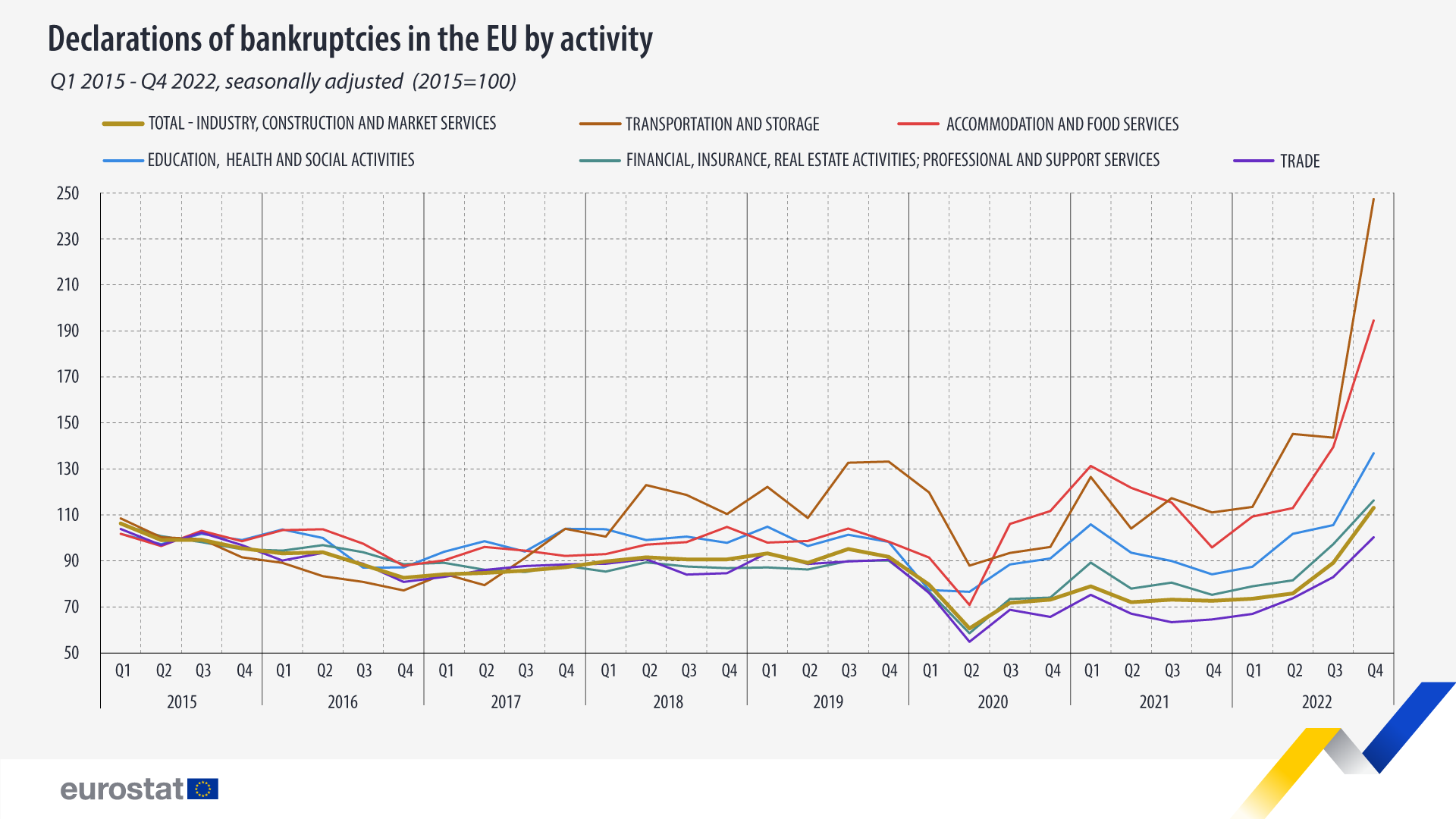

In 2022, inflation in the EU tripled to 9.2%, its highest reading ever. According to Eurostat, all economic sectors witnessed a rise in the number of bankruptcies in the fourth quarter of 2022 compared with the previous one. But the hardest hit sectors were transportation and storage (+72.2%), accommodation and food services (+39.4%), education, health and social activities (+29.5%), sectors that had already suffered significantly during the pandemic.

The contrast with the pre-pandemic bankruptcy rate is particularly striking. Compared to the fourth quarter of 2019 — the last quarter before the Covid-19 lockdowns and other pandemic restrictions came into effect — bankruptcies in the accommodation and food services sector surged by 97.7%, while the transportation and storage industry registered a similarly noteworthy 85.7% increase.

As I reported in February, companies in the United Kingdom, now a distinctly non-EU member, are hitting the wall at the fastest rate since the Global Financial Crisis. Much the same is happening across large parts of the European mainland.

The country that witnessed the highest rise (64%) in bankruptcies last year was Spain, whose economy actually grew by 4.7% according to the OECD. This can be partly explained by a new restructuring law enacted in late October, which simplifies and accelerates the debt restructuring process. Yet Spain also registered the second highest rise in bankruptcies in 2021, behind Romania. It is hoped that the insolvency rules will help reduce the country’s high bankruptcy rates, thereby attracting investment into the eurozone’s fourth-largest economy. For the moment it appears to be doing the opposite.

Another reason for the recent sharp rise in bankruptcies in Spain is that the obligation to file for bankruptcy was suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic to prevent an avalanche of business failures. This meant that many companies that would have hit the wall, including some longstanding zombie firms, were given a stay of execution. That suspension was lifted in July 2022. The result, as feared, has been an avalanche of business failures.

Other EU countries that have seen a notable increase in bankruptcies in 2022 include Austria (57%), France (51%), Belgium (42%), the Netherlands (18%) and Finland (8.5%). It is small and medium-size companies that are at the sharpest end of this trend. As Euractiv reported in January, insolvencies in France and across Europe have hurt small businesses, particularly one-person outfits, the most:

Yet [a report from data analytics consultancy] Altares… shows the situation is becoming increasingly worrying [for] larger SMEs with 10-99 employees.

“3,214 SME insolvencies were recorded in 2022 compared to 1,804 in 2021, a surge of +78% over one year,” the report reads. A third of these insolvencies occurred in the last three months of 2022, representing a 93% increase.

“When SMEs fall, it is the whole local economic network that is impacted,” Thierry Millon, who directed the study, told EURACTIV France.

“They can no longer pay their suppliers, and the job loss is much greater across the value chain,” he said. What’s of particular concern to him is that some of these SMEs were economically sound to start with before they were forced to unwind.

Soaring energy bills, low economic growth and the numerous financial constraints imposed by the repayment of state-guaranteed loans all contribute to this trend.

The “whatever it takes” era coined by President Emmanuel Macron to help companies by any means possible during the pandemic is also over.

This is a common theme in many countries: the financial, fiscal and furlough-based safety nets that were erected for businesses during the pandemic have long disappeared. A lot of the small in-person businesses that remained standing during the pandemic took on huge amounts of debt to weather the lockdowns and other restrictions, often for the first time. Once economies began reopening, not only did they have to start repaying those loans; they had to do so against a backdrop of surging input prices and, in some sectors, lacklustre demand.

Read the rest here: