The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is putting together a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) handbook to assist central banks and governments throughout the world in their CBDC rollouts.

Published publicly on April 10, the “IMF Approach to Central Bank Digital Currency Capacity Development” report outlines the IMF’s multi-year strategy for aiding CBDC rollouts, including the development of a living “CBDC Handbook” for monetary authorities to follow.

According to former People’s Bank of China deputy governor and current IMF deputy managing director Bo Li:

“The Handbook will be a compendium of knowledge and experience on CBDC. It will be the basis for capacity development and hopefully help countries make as well-informed decisions as possible when taking the major step to design and issue their own CBDC.”

According to the IMF, “The Handbook will mostly be descriptive rather than prescriptive, offering information, experience, empirical findings, and frameworks to evaluate CBDC.”

At present, the CBDC Handbook is intended for “medium- to high-level policymakers in central banks and ministries of finance, and to some extent in other government agencies.”

It is planned to be a living document, containing at least 19 chapters to be published incrementally over the next four to five years.

The Handbook will identify the most frequently asked questions related to CBDC, which include:

- Policy objectives and operational framework of CBDC

- Foundational requirements and readiness to issue CBDC, such as legal considerations, cyber resilience, central bank governance, and regulation and supervision

- CBDC design processes, considerations, and choices

- Project approaches and technology

- Potential macrofinancial impacts of CBDC

“The Handbook chapters will provide mostly a framework for structuring CBDC exploration, and recommendations will be drawn from international best practices and be conditional on country circumstances,” according to the report.

Chapters 8–11 may be of particular interest to citizens all over the world as they relate to issues of CBDC programmability, privacy concerns, and how law enforcement could access user data and freeze accounts.

For example, Chapter 8 “will identify design choices, such as operating model, limits in holding, programmability, interest bearing, and degree of centralization.”

Chapter 9 will delve into business models where “access to transactions data will likely play a key role” in how the “public sector can incentivize the private sector, such as banks, nonbank payment service providers, and technology vendors, to provide CBDC services.”

Chapter 10 is slated to focus on Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) while ensuring that “law enforcement bodies are able to investigate and prosecute offenses involving CBDC, or generating criminal proceeds in CBDCs, and seize, freeze, or confiscate such proceeds.”

And Chapter 11 “will consider the tradeoff between data use and privacy protection,” including “what data are generated by CBDC transactions and which institutions might have access to it.”

“In terms of anonymity, there would not be complete anonymity as there is with bank notes” — Christine Lagarde, European Central Bank, 2022

Speaking of data privacy, on September 27, France’s central bank — the Banque de France — held an international roundtable in which central bankers from the US and the EU confirmed that digital dollars and euros, should they go forward, would not be anonymous.

“In terms of anonymity, there would not be complete anonymity as there is with bank notes,” said Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank.

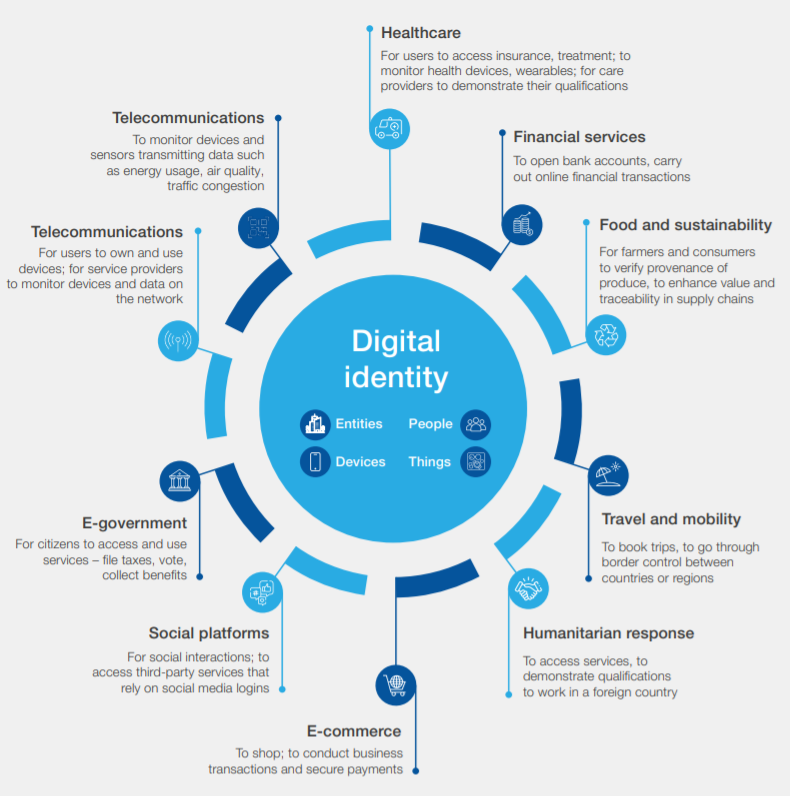

In other words, these CBDCs would require some form of digital identity scheme.

“This digital identity determines what products, services and information we can access – or, conversely, what is closed off to us” — Digital Identity Insight Report, World Economic Forum, 2018

A digital identity encompasses everything that makes you unique in the digital realm, and it is a system that can consolidate all of your most personal intimate data, including which websites you visit, your online purchases, health records, financial accounts, and who you’re friends with on social media.

It can be used to determine what products, services, and information are available to you, and it can certainly be used by public and private entities to deny you that access.

According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Annual Economic Report 2021, “The most promising way of providing central bank money in the digital age is an account-based CBDC built on digital ID with official sector involvement.”

Apart from the elimination of total anonymity, CDBCs also run the risk of having every transaction recorded while being fully programmable, which means financial institutions and their customers could have total control over where, when, and how your money is spent.

Bank of Russia deputy governor Alexey Zabotkin gave a real world example of what CBDC programmability could look like when he spoke at the annual cybersecurity training exercise Cyber Polygon back in 2021.

There, Zabotkin explained:

“This [digital ruble] will permit better traceability of payments and money flow, and also explore the possibility of setting conditions on permitted terms of use of a given unit of currency.

“Just imagine that you are able to give your kids some money in digital rubles and then restrict their use for purchase of junk food, for example.

“That would be a useful functionality for a customer, and of course you can come up with hundreds of other similar use cases.”

“Those who can associate the use of digital currency with programmability would be the intermediaries — would be the commercial banks” — Christine Lagarde, European Central Bank, 2023

Speaking at the BIS Innovation Summit in March 2023, Lagarde highlighted that central banks themselves had no interest in programming CBDCs but that commercial banks certainly did.

“For us [central banks], the issuance of a digital currency that would be central bank money would not be programmable — would not be associated with any particular limitation, whether it’s in time, in type of use — that to me would be a voucher. It wouldn’t be a digital currency,” said Lagarde.

“Those who can associate the use of digital currency with programmability would be the intermediaries — would be the commercial banks,” she added.

Concerning user anonymity and anonymous transactions, Lagarde conceded that “A digital currency will never be as anonymous and as protecting of privacy in many respects as cash, which is why cash will always be around.”

However, according to a World Economic Forum (WEF) Agenda blog post from September, 2017, the “gradual obsolescence of paper currency” is “characteristic of a well-designed CBDC.”

“A key difference with a CBDC is the central bank will have absolute control on the rules and regulations that will determine the use of that expression of central bank liability, and also, we will have the technology to enforce that” — Agustin Carstens, Bank for International Settlements, 2020

Speaking at an IMF seminar on October 19, 2020, BIS general manager Augustin Carstens explained that a major difference between CBDC and cash is that a CBDC gives the central bank both “absolute control” over the use of the CBDC, as well as the technology to enforce that control.

“We tend to establish the equivalence with cash, and there is a huge difference there,” Carstens said in 2020.

“For example, in cash we don’t know for example who’s using a 100 dollar bill today. We don’t know who is a 1,000 peso bill today.

“A key difference with a CBDC is the central bank will have absolute control on the rules and regulations that will determine the use of that expression of central bank liability, and also, we will have the technology to enforce that.

“Those two issues are extremely important, and that makes a huge difference with respect to what cash is,” he added.

“By programming CBDC, those [sic] money can be precisely targeted for what kind of people can own and what kind of use this money can be utilized” — Bo Li, IMF, 2022

In October 2022, IMF deputy managing director Bo Li, the same man now praising the CBDC Handbook, explained how CBDCs could be programmed.

“CBDC can allow government agencies and private sector players to program — to create smart contracts — to allow targeted policy functions. For example, welfare payment; for example, consumption coupons; for example, food stamps,” said Li.

“By programming CBDC, those [sic] money can be precisely targeted for what kind of people can own and what kind of use this money can be utilized,” he added.

Li also noted that institutions could take advantage of CBDC transactional data by following the model of Communist China where “non-traditional data can be very useful for financial service providers to give me a credit score.”

CBDCs, coupled with digital ID, erode the ability for citizens to transact anonymously.

As Willamette University College of Law assistant professor Rohan Grey testified in the US House of Representatives in June 2021, “Transactional anonymity, like anonymity more broadly, is a public good and a core bedrock of political freedom in a democratic society.”

Ultimately, a CBDC linked with digital ID could allow governments and corporations to put permissions on what you can buy with your own money, including expiration dates on when you can spend it.

It is a system ripe for total surveillance and control over many aspects of society, and it paves the way for an authoritarian system of social credit that incentives, coerces, otherwise manipulates citizen behavior.

With its upcoming CBDC Handbook, the IMF now has a multi-year plan to assist central banks and governments all over the world to implement what may spell the end of financial freedom and autonomy as we know it.