Like many of you, I watched parts of Vera Sharav’s new documentary series, Never Again is Now Global, this week. With its sharp focus on the Holocaust and Nazi tactics in general, I felt the need to reach back into some of my older research and remind readers who was supporting and enabling the rise of Hitler.

Spoiler alert: It is the same class of folks responsible for tyranny today.

What we’re taught about the years leading up to the Second World War involves alleged appeasement of the Third Reich, e.g. if only the Allies were stronger in their resolve, the Axis powers could have been stopped.

Perhaps the first step in challenging this so-called analysis would be to demonstrate that it wasn’t appeasement that took place prior to WWII. It was, in the best cases, indifference. More often, it was a collaboration based on economic greed and more than a little shared ideology.

The pursuit of profit long ago transcended national borders and national loyalty. In the decades before WWII, doing business with Hitler’s Germany or Mussolini’s Italy (or, as a proxy, Franco’s Spain) proved no more unsavory to the captains of industry than selling military hardware to Saudi Arabia does today. What’s a little repression when there are boatloads of money to be made?

In other words, when William E. Dodd, US ambassador to Germany during the 1930s, declared “a clique of US industrialists is working closely with the fascist regime[s] in Germany and Italy,” he wasn’t kidding.

“Many leaders of Wall Street and of the US foreign policy establishment had maintained close ties with their German counterparts since the 1920s, some having intermarried or shared investments,” says investigative reporter Christopher Simpson. “This went so far in the 1930s as the sale in New York of bonds whose proceeds helped finance the Aryanization of companies and real estate looted from German Jews. US investment in Germany accelerated rapidly after Hitler came to power.”

Such investment increased “by some 48.5 percent between 1929 and 1940, while declining sharply everywhere else in continental Europe.”

Among the US corporations that invested in Germany during the 1920s were Ford, General Motors, General Electric, Standard Oil, Texaco, International Harvester, ITT, and IBM — all of whom were more than happy to see the German labor movement and working-class parties smashed.

For many of these companies, operations in Germany continued during the war (even if it meant the use of concentration-camp slave labor) with overt US government support.

“Pilots were given instructions not to hit factories in Germany that were owned by US firms,” writes Michael Parenti. “Thus Cologne was almost leveled by Allied bombing but its Ford plant, providing military equipment for the Nazi army, was untouched; indeed, German civilians began using the plant as an air raid shelter.”

International Telegraph and Telephone (ITT) was founded by Sosthenes Behn, an unabashed supporter of the Führer even as the Luftwaffe was bombing civilians in London. ITT was responsible for creating the Nazi communications system, along with supplying vital parts for German bombs.

According to journalist Jonathan Vankin, “Behn allowed his company to cover for Nazi spies in South America, and one of ITT’s subsidiaries bought a hefty swath of stock in the airline company that built Nazi bombers.”

Behn himself met with Hitler in 1933 (the first American businessman to do so) and became a double agent of sorts. While reporting on the activities of German companies to the US government, Behn was also contributing money to Heinrich Himmler’s Schutzstaffel (SS) and recruiting Nazis onto ITT’s board.

In 1940, Behn entertained a close friend and high-ranking Nazi, Gerhard Westrick, in the United States to discuss a potential U.S.-German business alliance — precisely as Hitler’s blitzkrieg was overrunning most of Europe and Nazi atrocities were becoming known worldwide.

In early 1946, having relied on the Dulles brothers to survive his open flirtation with Nazi Germany, instead of facing prosecution for treason, Behn ended up collecting $27 million from the US government for “war damages inflicted on its German plants by Allied bombing.” He was in the perfect position to lobby President Truman concerning the newly formed Central Intelligence Group (CIG).

Meeting with the chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral William D. Leahy, in the White House, Behn, as recorded in Leahy’s diary, generously offered for consideration “the possibility of utilizing the service of [ITT’s] personnel in American intelligence activities.”

In December 1933, Standard Oil of New York invested one million dollars in Germany for the making of gasoline from soft coal. Undeterred by the well-publicized events of the next decade, Standard Oil also honored its chemical contracts with I.G. Farben — a German chemical cartel that manufactured Zyklon-B, the poison gas used in the Nazi gas chambers — right up until 1942.

Other companies that traded with the Reich and, in some cases, directly aided the war machine, before and during this time, included the Chase Manhattan Bank, Davis Oil Company, DuPont, Bendix, Sperry Gyroscope, and the aforementioned General Motors GM top man William Knudsen called Nazi Germany “the miracle of the 20th century.”

On the governmental front, US Secretary of State Breckinridge Long curiously gave the Ford Motor Company permission to manufacture Nazi tanks while simultaneously restricting aid to German-Jewish refugees because the Neutrality Act of 1935 barred trade with belligerent countries.

Miraculously, this embargo did not include petroleum products and Mussolini’s Italy tripled its gasoline and oil imports in order to support its war effort while Texaco exploited this convenient loophole to cozy up to Spain’s resident fascist, Generalissimo Francisco Franco.

And then there was Sullivan and Cromwell, the most powerful Wall Street law firm of the 1930s.

John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles — the two brothers who guided the firm; the same two brothers who boycotted their own sister’s 1932 wedding because the groom was Jewish — served as the contacts for the company responsible for the gas in the Nazi gas chambers, I.G. Farben.

During the pre-war period, the elder John Foster led off cables to his German clients with the salutation “Heil Hitler,” and he blithely dismissed the Nazi threat in 1935 in a piece he wrote for the Atlantic Monthly. In 1939, he told the Economic Club of New York, “We have to welcome and nurture the desire of the New Germany to find for her energies a new outlet.”

“Hitler’s attacks on the Jews and his growing propensity for territorial expansion seem to have left Dulles unmoved,” writes historian Robert Edward Herzstein. “Twice a year, [Dulles] visited the Berlin office of the firm, located in the luxurious Esplanade Hotel.”

Ultimately, it was little brother Allen who actually got to meet the German dictator, and eventually smoothed over the blatant Nazi ties of ITT’s Sosthenes Behn.

“(Allen) Dulles was an originator of the idea that multinational corporations are instruments of U.S. foreign policy and therefore exempt from domestic laws,” Vankin writes. This idea later took root in U.S.-dominated institutions and agreements like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and World Trade Organization.

Leonard Mosley, the biographer of the Dulles brothers, defended Allen by evoking the never-fail, all-purpose alibi of anti-communism. The younger Dulles, Mosley claimed, “made his loathing of the Nazis plain, years before World War II…(it was) the Russians (who tried) to link his name with bankers who financed Hitler.”

However, in 1946, both brothers would play a major role in the founding of the United States intelligence community and the subsequent recruiting of Nazi war criminals.

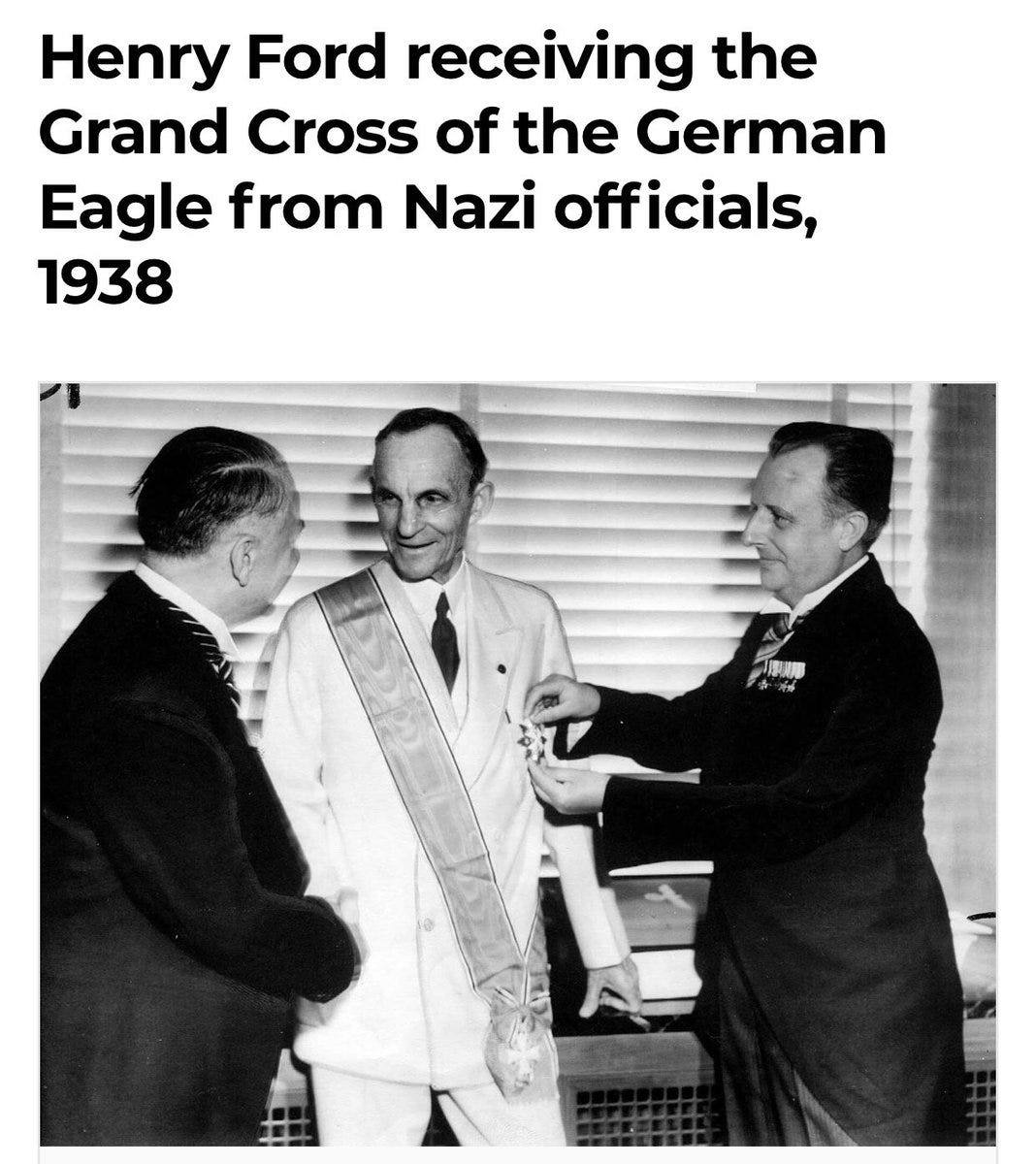

One Third Reich supporter who never required a disclaimer was Henry Ford, the autocratic magnate who despised unions, tyrannized workers, and fired any employee caught driving a competitor’s model. Ford, an outspoken anti-Semite, believed that Jews corrupted gentiles with “syphilis, Hollywood, gambling, and jazz.” In 1918, he bought and ran a newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, which became an anti-Jewish forum.

“The New York Times reported in 1922 that there was a widespread rumor circulating in Berlin claiming that Henry Ford was financing Adolf Hitler’s nationalist and anti-Semitic movement in Munich,” write James and Suzanne Pool in their book Who Financed Hitler. “Novelist Upton Sinclair wrote in The Flivver King, a book about Ford, that the Nazis got forty thousand dollars from Ford to reprint anti-Jewish pamphlets in German translations, and that an additional $300,000 was later sent to Hitler through a grandson of the ex-Kaiser who acted as intermediary.”

An appreciative Adolf Hitler kept a large picture of the automobile pioneer beside his desk, explaining: “We look to Heinrich Ford as the leader of the growing Fascist movement in America.” Hitler hoped to support such a movement by offering to “import some shock troops to the U.S. to help [Ford] run for president.”

In 1938, on Henry Ford’s 75th birthday, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Supreme Order of the German Eagle from the Führer himself. He was the first American (GM’s James Mooney would be second) and only the fourth person in the world to receive the highest decoration that could be given to any non-German citizen.

An earlier honoree was none other than a kindred spirit, Benito Mussolini.

Speaking of Mussolini, that particular blacksmith’s son also merited the attention of US businessmen and lawmakers alike. Il Duce (“the leader”), exploiting the fears of an anti-communist ruling class in Italy, installed himself as head of the single-party fascist state in 1925 after declaring three years earlier that, “either they will give us the government or we shall take it by descending on Rome” and “We stand for a new principle in the world. We stand for the sheer, categorical, definitive antithesis to the world of democracy.”

Putting this doctrine into action, Mussolini took aim at Italy’s powerful unions. The solution was to smash unions, political organizations, and civil liberties. This included the destruction of labor halls, the shutting down of opposition newspapers, and unions and strikes were outlawed in both Italy and Germany. Union property and farm collectives were confiscated and handed over to rich private owners. Even child labor was reintroduced in Mussolini’s Italy.

Despite or perhaps because of the Blackshirts, the terror tactics, the smashing of democratic institutions, and the blatant fascist posturing, Mussolini received some rave reviews on both sides of the Atlantic.

“It is easy to mistake, in times of political turmoil, the words of a disciplinarian for those of a dictator. Mussolini is a severe disciplinarian, but no dictator,” wrote New York Times senior foreign correspondent, Walter Littlefield, in 1922.

Further serving the corporate roots of the US media, Littlefield went on to advise that “if the Italian people are wise, they will accept the Fascismo, and by accepting [they will] gain the power to regulate and control it.” Six days earlier, an unsigned Times editorial observed that “in Italy as everywhere else, the great complaint against democracy is its inefficiency . . . Dr. Mussolini’s experiment will perhaps tell us something more about the possibilities of oligarchic administration.”

In January 1927, Winston Churchill wrote to Il Duce, gushing “if I had been an Italian, I am sure I would have been entirely with you from the beginning to the end of your victorious struggle against the bestial appetites and passions of Leninism.” Even after the advent of war, Churchill still found room in his heart for the Italian dictator, explaining to Parliament in 1940: “I do not deny that he is a very great man but he became a criminal when he attacked England.”

Other unabashed apologists for Dr. Mussolini included:

-

Richard W. Child, former ambassador to Rome, stated in 1938: “it is absurd to say that Italy groans under discipline. Italy chortles with it! It is the victor! Time has shown that Mussolini is both wise and humane.”

-

The House of Morgan loaned $100 million to the Italian government in the late 1920s and then reinvested it in Italy upon its repayment.

-

Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, who, also in the late 1920s, renegotiated the Italian debt to the U.S. on terms more favorable by far than those obtained by Britain, France, or Belgium.

- Governor Philip F. La Follette of Wisconsin (considered presidential timber in the 1930s) kept an autographed photo of Il Duce on his wall.

-

A 1934 Cole Porter song originally contained the lyrics, “You’re the tops, you’re Mussolini.” It was eventually changed to “the Mona Lisa.”

-

As late as 1940, 80 percent of the Italian-language dailies in the U.S. were pro-Mussolini.

Finally, there was FDR himself who, well into the 1930s, was “deeply impressed” with Benito Mussolini and referred to the Italian ruler as that “admirable Italian gentleman.”

Despite Roosevelt’s positive assessment of the strongman of Italian fascism, there is evidence that some home-grown fascists may have cautiously explored the option of an American coup.

As a certain “admirable Italian gentleman” once declared, “Fascism is corporatism.”

Despite committing atrocities, countless murderers, strong men, and dictators have received overt and covert support from the West in general and the US in particular… all in the name of profit and power.

Take-home message: When (accurately) comparing some current tactics to those used by the Nazis, never forget who supported those Nazis — and still do.