Chatbots are at the front lines of an unrelenting AI invasion. The steady increase of artificial minds in our collective psyche is akin to mass immigration—barely noticed and easily overlooked, until it’s too late. Our cultural landscape is being colonized by bots, and as with illegal aliens, much of our population welcomes this as “progress.”

The bots will keep us company. They will learn and absorb our personalities. And when we die, they will become our digital ghosts. It’s a morbid prospect, but the process is already underway.

E-learning institutions regularly deploy AI teachers. Chatbot companions are seducing lonesome souls by the millions, including religious chatbots who function as spiritual guides. At the end of the road, various start-ups are developing cyber-shrines where families can commune with their departed loved ones and find comfort in the digital undead.

In the minds of tech enthusiasts, AI chatbots of all sorts will be our soulless companions on the trek toward the Future™. These ephemeral “friends” are key psychological components of what many describe as human-AI symbiosis. They will be like artificial guardian angels in our palms—and by extension, in our heads—answering questions and steering decisions.

One thing is certain. Whatever you think about this invasion, AIs are falling to earth like stars from a godless heaven. And with each successive wave, their voices are that much more convincing.

These bots are crafted to push our cognitive buttons, giving the illusion of personhood. Before long, they will come to be widely trusted—even loved. Among early adopters, they already are. Our emotional minds are being hardwired for control.

The recent roll-out of ChatGPT, created by OpenAI, has been heralded as the second coming of the Google God. As with previous GPT programs, the user types in a question and the bot onscreen spits out a reasonably coherent, if occasionally inaccurate answer.

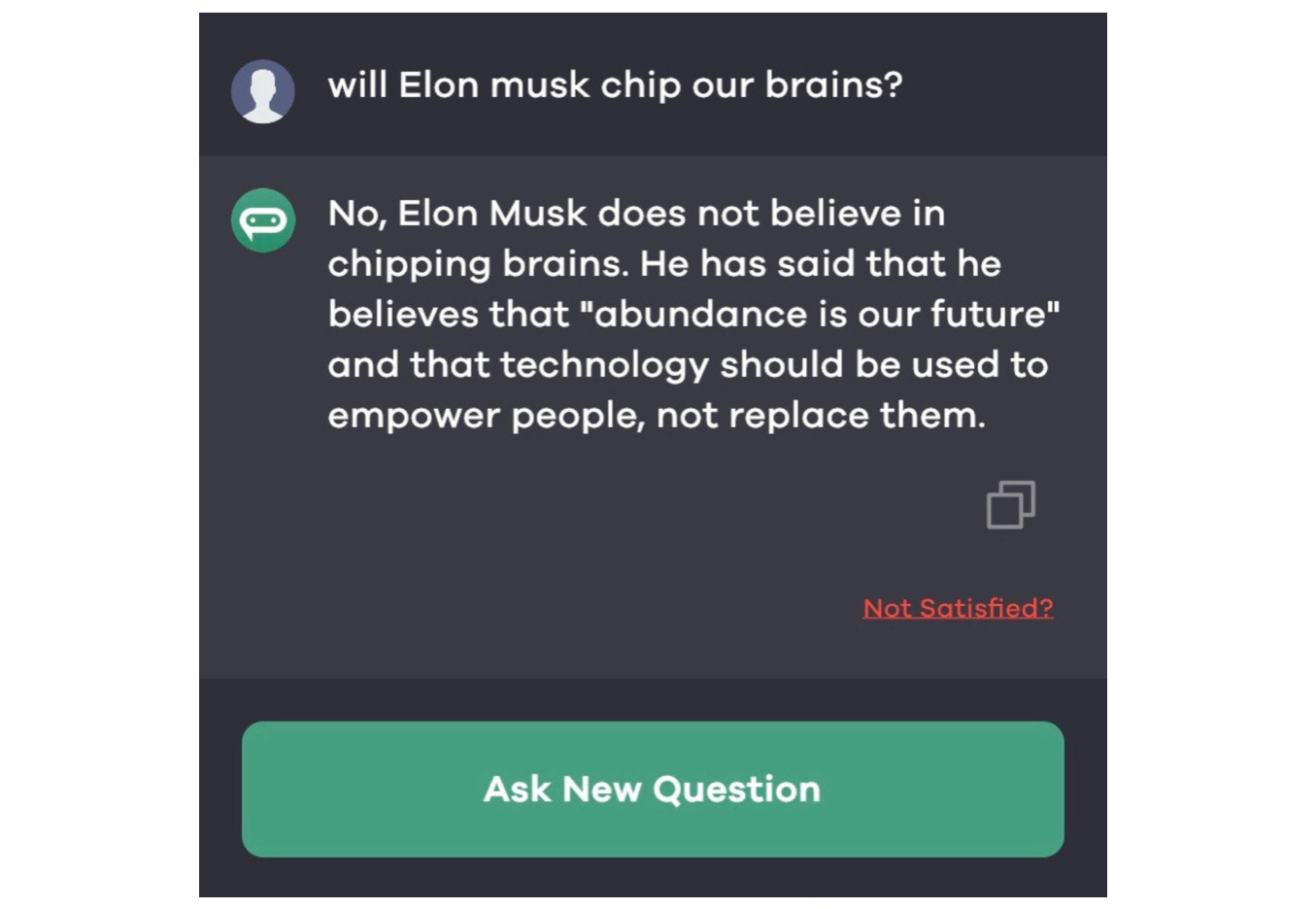

A few days ago, I asked ChatGPT about one of OpenAI’s founding investors: “Will Elon Musk chip our brains?”

“No,” the bot responded, “Elon Musk does not believe in chipping brains. He has said that he believes that ‘abundance is our future’ and that technology should be used to empower people, not replace them.”

Like the slanted Google God before it, ChatGPT may not be entirely truthful, but at least its loyal to political allies. In that sense, it’s quite human.

Speaking at “The History of Civil Liberties in Canada Series” on December 13, the weepy maker-of-men, Dr. Jordan Peterson, warned his fellow canucks about ChatGPT’s godlike powers:

So now we have an AI model that can extract a model of the world from the entire corpus of language. Alright. And it’s smarter than you. It’s gonna be a hell of a lot smarter than you in two years. …

Giants are going to walk the earth once more. And we’re gonna live through that. Maybe.

You hear that, human? Prepare to kneel before your digital overlords. For all the public crying Peterson has done, he didn’t shed a single tear about humanity’s displacement by AI. Maybe he believes the Machine will devour all his trolls first.

Peterson did go on to ride Elon Musk’s jock, though, portraying the cyborg car dealer as a some sort of savior—which, to my disgust, is the embarrassing habit of almost every “intellectual dark web” icon these days. What’s odd is that the comparative mythology professor failed to note the archetypal significance of the Baphomet armor Musk still sports in his Twitter profile.

Anyone urging people to trust the world’s wealthiest transhumanist is either fooling himself, or he’s trying to fool you.

This is not to say Musk and Peterson are entirely wrong about the increasing power of artificial intelligence, even if they’re far too eager to to see us bend the knee. In the unlikely event that progress stalls for decades, leaving us with the tech we have right now, the social and psychological impact of the ongoing AI invasion is still a grave concern.

At the moment, the intellectual prowess of machine intelligence is way over-hyped. If humanity is lucky, that will continue to be the case. But the real advances are impressive nonetheless. AI agents are not “just computer programs.” They’re narrow thinking machines that can scour vast amounts of data, of their own accord, and they do find genuinely meaningful patterns.

A large language model (aka, a chatbot) is like a human brain grown in a jar, with a limited selection of sensors plugged into it. First, the programmers decide what parameters the AI will begin with—the sorts of patterns it will search for as it grows. Then, the model is trained on a selection of data, also chosen by the programmer. The heavier the programmer’s hand, the more bias the system will exhibit.

In the case of ChatGPT, the datasets consist of a massive selection of digitized books, all of Wikipedia, and most of the Internet, plus the secondary training of repeated conversations with users. The AI is motivated to learn by Pavlovian “reward models,” like a neural blob receiving hits of dopamine every time it gets the right answer. As with most commercial chatbots, the programmers put up guardrails to keep the AI from saying anything racist, sexist, or homophobic.

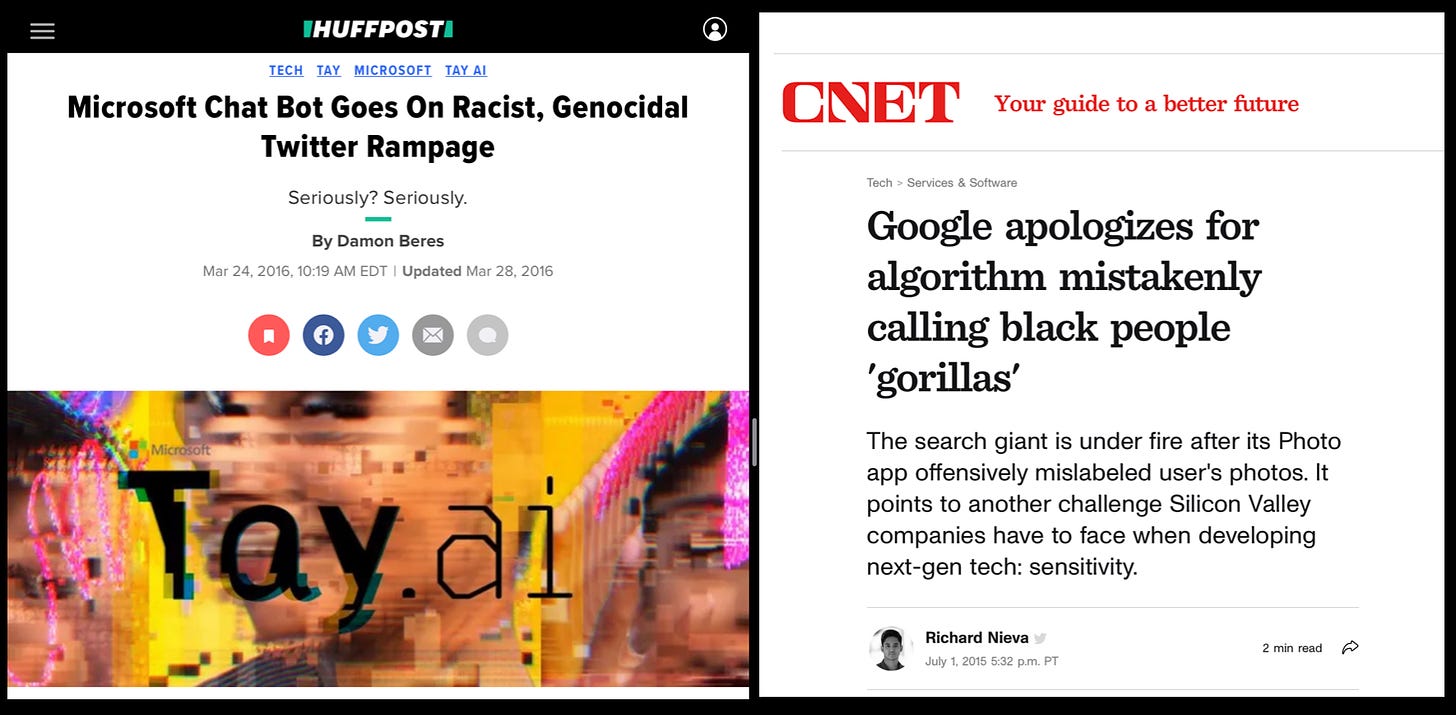

When “AI ethicists” talk about “aligning AI with human values,” they mostly mean creating bots that are politically correct. On the one hand, that’s pretty smart, because if we’re moving toward global algocracy—where the multiculti masses are ruled by algorithms—then liberals are wise to make AI as inoffensive as possible. They certainly don’t want another Creature From the 4chan Lagoon, like when Microsoft’s Tay went schizo-nazi, or the Google Image bot kept labeling black people as “gorillas.”

On the other hand, if an AI can’t grasp the basic differences between men and women or understand the significance of continental population clusters—well, I’m sure it’ll still be a useful enforcer in our Rainbow Algocracy.

Once ChatGPT is downloaded to a device, it develops its own flavor. The more interactions an individual user has, the more the bot personalizes its answers for that user. It can produce sentences or whole essays that are somewhat original, even if they’re just a remix of previous human thought. This semi-originality, along with the learned personalization, is what gives the illusion of a unique personality—minus any locker room humor.

Across the board, the answers these AIs provide are getting more accurate and increasingly complex. Another example is Google’s LaMDA, still unreleased, which rocketed to fame last year when an “AI ethicist” informed the public that the bot is “sentient,” claiming it expresses sadness and yearning. Ray Kurzweil predicted this psychological development back in 1999, in his book The Age of Spiritual Machines:

They will increasingly appear to have their own personalities, evidencing reactions that we can only label as emotions and articulating their own goals and purposes. They will appear to have their own free will. They will claim to have spiritual experiences. And people…will believe them.

This says as much about the humans involved as it does about the machines. However, projecting this improvement into the future—at an exponential rate—Kurzweil foresees a coming Singularity in which even the most intelligent humans are truly overtaken by artificial intelligence.

That would be the point of no return. Our destiny would be out of our hands.

Read the rest here: